Uncanny Valley is the type of game that I will remember more fondly a year from now than I do right now, a few days after finishing it. Cowardly Creations has crafted a small world that is going to burrow its way into the back of my brain and lay eggs just before its untimely death.

Uncanny Valley is a 2D survival horror game that isn’t easy to fit into a categorical box; while it is tempting to compare it to other indie sidescrollers such as Lone Survivor and Home, there are key differences that set the three titles apart. Whereas the latter two games require you to get from one point to another, the former is more about observation and exploration — at least in the first half. The second half changes up the formula, and ultimately damages the experience as a whole. More on that later.

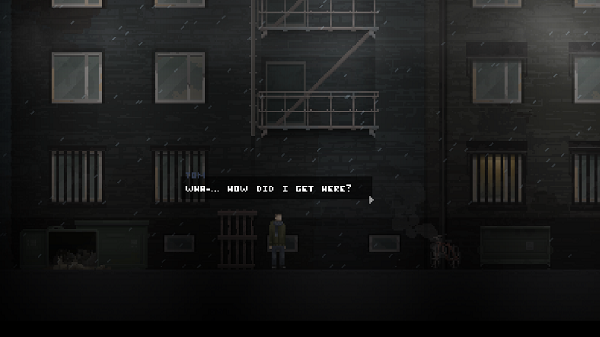

Players assume the role of Tom, a man trying to leave a troubled past behind by becoming a new security guard at the Melior robotics facility. The facility is abandoned aside from Tom’s fellow guard, Buck, and the facility’s groundskeeper, Eve. Every night, you have a set amount of time to explore Melior during your guard duties. You have seven real-time minutes representing an entire shift, and it’s up to you to use that time wisely. Uncanny Valley likes to play it quiet and let you figure out what to do all on your own, which doesn’t always work out well. It’s easy to get caught up in reading the exposition found in both company emails and (surprisingly well-voiced) cassette tapes on your first night without realizing that you’re timed. Once you understand that time is finite, the mechanic becomes interesting in that you start prioritizing what you want to get done each night.

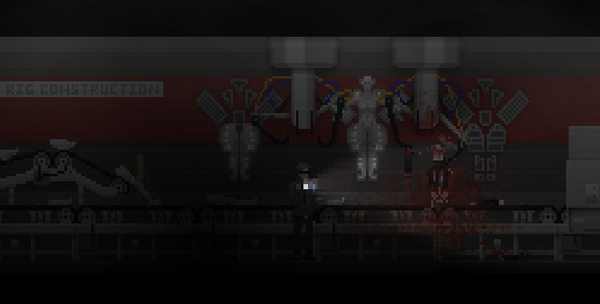

The first nights are composed of light puzzle-solving and delving into Uncanny Valley‘s universe. After every shift you are able to go to bed and face one of Tom’s short dreams, ranging from chase sequences to flashbacks that fill you in on story beats. Without spoiling the plot’s main conceit, once the first few nights have passed, the game becomes a more traditional survival horror game. Tom finds a weapon and has to fight his way out and unravel Melior’s mysteries. There’s a creative location-based damage/healing system that enables enemies to hurt Tom in specific areas, inflicting status effects such as the inability to crouch if your leg is broken. This takes away the fail state of death that is common in horror games, though if you’re severely damaged enough times you get a gruesome alternate ending that’s probably going to haunt me for awhile. What’s strange about this second phase of the game is how short it is; though Uncanny Valley is short in general (probably two hours for a playthrough at the most), it feels like just when the puzzles, combat, and damage system all start to come together, the game ends. With branching paths and multiple endings, the game is built for multiple playthroughs, but it still feels like it comes to abrupt halt after gaining steam.

The Consequence System is what fuels the need for multiple playthroughs. Depending on how you use your time, solve certain puzzles, and interact with the other characters, you can find yourself in various situations leading to five different endings. I stumbled across my first ending on accident and was confused as hell, wondering if I missed something. It turns out that I did — I missed the entire middle segment of the story. I hadn’t been paying attention to the small choices I was making, and I paid for it. Having to replay the opening segments over and over to get all of the endings was initially frustrating, but halfway through my time with the game a patch was released that allowed you to both speed up dialogue and sleep through days to skip them. This made earning the other endings a vastly more tantalizing prospect.

Overall, the plot doesn’t go anywhere too surprising but it is engaging enough to keep you poking through Melior. Danilo Kapel’s score stands outs and propels Uncanny Valley’s atmosphere into the stratosphere. There are shades of the icy electronics of Atticus Finch and Trent Reznor’s work on The Girl with a Dragon Tattoo, and it works perfectly when you’re crunching snow under your boots as you walk from your in-game apartment back to the facility for another shift. The way the score aligns with the aforementioned bloody ending is stellar.

What prevents Uncanny Valley from being the best version of itself is an amalgamation of small issues that threaten to undo Cowardly Creations’ good work. Typos are everywhere, and though they can be waved away when you find them in emails, finding them in dialogue and on signs in rooms towards the end of the game gets a bit silly. Different rooms have different levels of zoom on Tom, and the UI changes size depending on the room you’re in. This doesn’t sound like a huge deal, but when you’re reading emails as your primary form of storytelling for a large portion of the experience, it becomes tiresome. While it’s nice to see a game that doesn’t want to hold your hand, it’s also aggravating having to find keycards with a time limit and not much in the way of direction. Collectible items can also be difficult to spot at times. Maybe I just suck at games. Maybe I’m losing my eyesight. I don’t know.

A little more time in the oven could have done wonders for Uncanny Valley, which is made evident by how much the patch helped to improve the game. Being able to skip through days and speed through dialogue alone were issues that felt like oversights, so I’m glad to see that Cowardly Creations is working quickly to correct these problems. Controller support is also on its way, which seems like it will be a good fit but is coming too late to factor into this review. Most of Uncanny Valley‘s mistakes are small and seem to be the results of a small independent studio feeling its way around; they’re endearing and understandable but still detract from the experience. I can’t wait to see what these guys will do next.

(7.5 / 10)

(7.5 / 10)

Good

(7.5 / 10)

(7.5 / 10)

ZackFurniss

ZackFurniss