If you’re a fan of this site, then you might already know about my notorious knack for being unafraid of modern horror games. You may believe that there’s a humorous wisp of irony about me writing for a horror gaming site and all, but I think this defunct wiring gives me a unique position at sniffing out the most impressive and extraordinary specimens within the genre. It is with this talent that I approached Red Barrel’s Outlast for review. Already deemed one of the “scariest games ever” during previews, Outlast became a personal challenge for myself. Will its development team of former Ubisoft talent be able to craft a horror title that can inflict fear in someone like myself? Well, the answer lies below [scary thunder sound].

Outlast follows investigative journalist Miles Upshur as he investigates a lead at the Mount Massive Asylum and its connections to the notoriously unethical Murkoff Corporation. Equipped with just a video camera and an infrared camera light, Miles infiltrates the asylum looking for his next story. It isn’t long until the seemingly abandoned asylum starts to reveal clues of a terrible event that has passed. Armed with only the power to see in the dark thanks to his video camera, Miles has to explore the asylum and find his way to freedom against disturbing and unexplained forces.

Throughout the course of the game, Miles will find documents with background information on the asylum and its staff or residents. If certain areas or events are captured on camera, Miles will produce his own diary entry with what he’s thinking about. The documents, as expected in a robust survival horror experience create more questions than answers. Mount Massive Asylum’s secret slowly gets exposed, but it’s still easy to want more from the game’s universe even after completion. With Mile’s being a silent protagonist—aside from his audible signs of fear–, his diary acts as a way to introduce players to his personality. There were some instances where I could agree with Miles, but there were others where I didn’t get the sense that I could relate to him all too well. Perhaps this was due to the contrasting style of “imagine yourself as the player” and seeing what Miles’ thinks of a situation. But such is a small grievance.

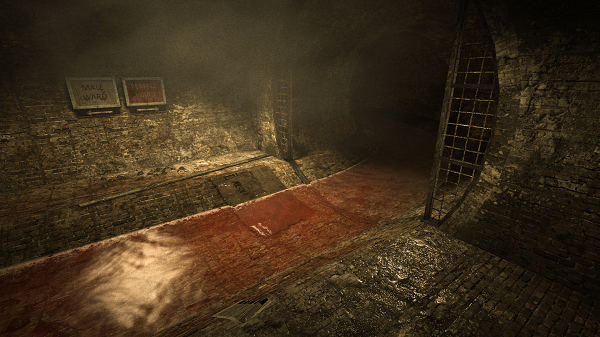

To say that Outlast is a great looking game would be an understatement. When confronted with a game that takes place in one type of environment, one could suspect that level design would eventually become repetitive and uninteresting. In the case of Outlast, Red Barrel’s excelled at creating a beautifully crafted world that permeates tension, horror, and the insanity of its residents. Marveling at the attention to detail and imagery found in Mount Massive Asylum is hard to avoid. It isn’t just a scary dead body or a pool of blood that puts a chill in your spine; it’s the lighting, texture detail, and the player’s focal point all being perfected into something that will deeply unsettle players.

It is quite apparent very early on that Outlast‘s level design and their respective objectives were strenuously tested for the most organic response from players. Environments, while unique and unfamiliar, all share a level of polish that makes navigation extremely approachable for new players of the game. Focus testing to this degree is highly appreciated as it does not compromise the challenge of moving through areas filled with potential threats, nor limit the visual variety seen in levels. This is especially important due to the nature of gameplay within Outlast.

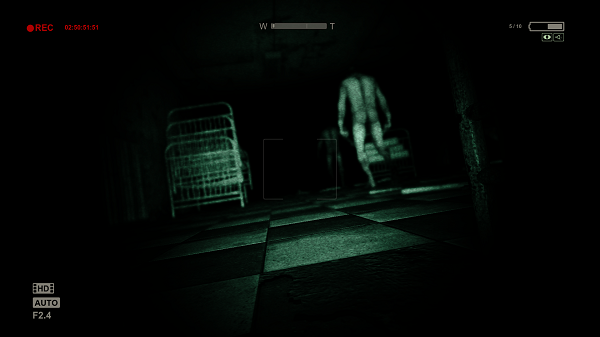

Miles is no fighter, and because of this, his tactics to avoid being killed by Mount Massive’s residents include stealth and quick navigation through environments via climbing, crawling, or jumping. I think Mile’s athleticism was a little overplayed during previews, but you can expect actions such as climbing a surface to reach an open vent for escape, hiding under a desk, or hanging outside of a window to avoid detection. Outlast‘s stealth elements are to-the-point; hiding in the dark is a decent method of remaining unseen, but only at a certain distance. Hiding out of the line of sight behind or under something is the method of staying safe, but doing so too slowly will allow a pursuer to quickly deduce where Miles is hiding.

Exploring or working toward an objective in hostile areas is where a lot of tension comes from in this game. Enemies, whether looking for you specifically or anything to fixate their lust for violence on, patrol in patterns. Being mindful of these patterns while moving slowly and in the dark keeps Miles away from a pipe to the head or knife through the chest. The use of night vision mode on the camera is essential in this game and alongside stealth. What I especially enjoyed about the camera was its range of focus. Objects, unless zoomed in on, will not be in full focus, causing the imagination to go wild with hostile possibilities. In night vision mode, blobs of black and green far off in the distance can easily perturb players and make them feel like an enemy is just a few feet away. It’s a fantastic visual element that amplifies the foreboding qualities of the asylum.

The patients of Massive Asylum come in many flavors. There’s the hostile and the docile, and maybe a few in between. Players will quickly notice that they’re not dealing with a few insane people with attitudes. Horribly disfiguring tests have been performed on the patients, creating an unsettling community of deranged individuals. Behaviorally, there are many scenes where Miles will end up in populated areas where the residents of the asylum showcase their feelings in the most psychotic ways. You may see one crying in the corner, another acting animalistic, and another doing rounds of bashing his head against the wall. There are even a few that may look horrifying and mutilated, but still retain enough sanity to want to help Miles (which made me a little sad, to be honest). It’s this behavior that truly shines creatively; Red Barrel’s created a bunch of believably certifiable folk that successfully unsettled myself. Then, there’s the unique patients that you’ll meet through the game—the special characters with their own shining personalities. I won’t spoil it for you, but have fun with The Twins.

Going back to the level of refinement seen in this game, Red Barrels also spent a lot of time implementing the right amount and types of scares. The game starts off with a fairly generic jump scare, but the team managed to add a variety of fright moments that don’t end up feeling retread. One of my favorite scare moments was skillfully underplayed, where a sudden figure ends up in the line of sight, a person or thing taking a quick look at Miles before wandering off. It’s so quick, so mild, but it destroys any feeling of comfort and all notions of what kind of scares Outlast will reveal next.

Outlast brings together industry talent that has worked on such titles as Prince of Persia, Splinter Cell, and Assassin’s Creed. Crafted by developers behind such great games, one would expect Outlast to be exceptional, and thankfully it is; beyond even what I expected. Outlast is a chef d’oeuvre within the survival horror genre. Its mechanics, simple. Its ability to scare the player via the fear or impending terror, wonderfully viscous and masterful. This is a game that I will admit put me on edge quite a bit. I can’t recommend it enough.

(10 / 10)

(10 / 10)

The Holy Grail

(10 / 10)

(10 / 10)

cjmelendez_

cjmelendez_