It’s not very often that a game comes along that changes a paradigm or moves the art form forward in a big way. Immortality is definitely one of those games that transcends the medium. There’s a hell of a lot to talk about, even if a good amount of the story details won’t be shared here to avoid spoilers and lessening the experience for future players.

If you haven’t heard of the game’s writer and creator, Sam Barlow, he’s a life-long horror fan who got his start in horror gaming as the main writer and designer for Silent Hill: Origins in 2007 and the fan-favorite Silent Hill: Shattered Memories in 2009. He then went on to create a series of narrative-focused live-action detective games, including Her Story and Telling Lies.

While all of Sam’s recent FMV games outside of Silent Hill have had elements of the weird or eerie from time to time, none of them have doubled down on the psychological horror aspects that were so heavily featured in his Silent Hill titles. However, as proclaimed in some developer diaries over the last two years, Immortality was touted as his full return to the horror genre and creating a project that was fully his from the ground up, by also self-publishing a game for the first time.

To say that every tiny element and detail surrounding the production of this game is deeply purposeful and meticulously thought-out is an understatement, even with the higher-level elements like the design of the website and the framing of the story. Every picture, every frame, and every word has layers upon layers of meaning that usually won’t become clear until long after your first encounter with it, with pacing so perfectly balanced, and nuanced, and which causes an immense amount of immersion for the player, driving one to seek understanding as more details and contexts are revealed.

To start with the meta-aspects of the game first, even the title of the game and the main tagline end up having many multiple meanings and layers as the story unfolds. Cleverly, Immortality poses its main tagline as a question: “What happened to Marissa Marcel?” The act of framing the entire experience with a question gives you only the tiniest glimpse of the amount of mystery you’ll be delving into, and similar to the iconic Twin Peaks‘ “Who killed Laura Palmer?” the question ends up essentially being the tip of the iceberg of what will become an overwhelmingly large and complex web of narrative you’ll be leaping into in the search for answers to this question.

Speaking of Twin Peaks, it’s safe to say that some of the biggest influences for Immortality, among dozens of others throughout the history of literature, film, television, and video games, would be projects and creators from the classic age of avant-garde and exploratory cinema of the 1960s-1990s. These influences include David Lynch, Alfred Hitchcock, William Friedkin, Dario Argento, Paul Schrader, and many more in the same vein (coincidently a list of what I also consider to be the most important and influential creators/projects in the history of their respective mediums.)

The further framing of the story and where the player fits into this story is an even more intriguing and enthralling layer to the whole experience since the story that you’re given at the start is that there was an actress named Marissa Marcel who shot to stardom quickly in the late 1960s and ended up only starring in three films between the years of 1968 and 1999, but none of these three films were actually released. The location of the unedited footage from the making of these films has remained unknown until 2022, when it was obtained and presented to you, who will act as the film editor (an in turn, a detective of sorts,) trying to find out what happened to this actress who mysteriously disappeared for long periods of time after her various film projects were canceled and where she might be now, in 2022.

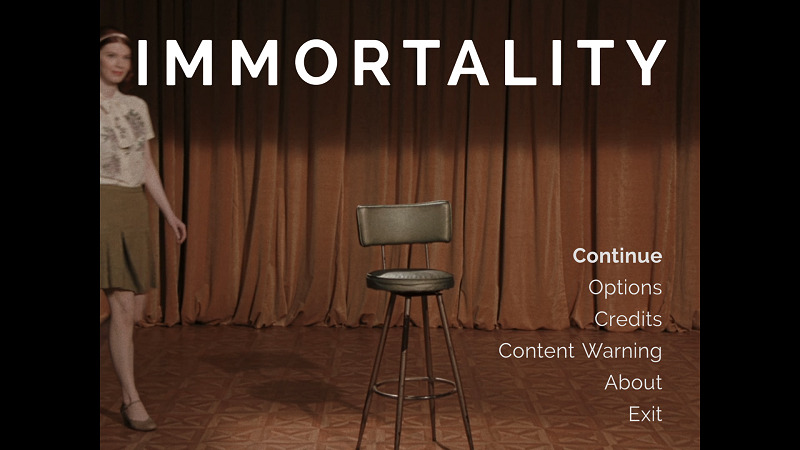

The game starts with you sitting down at a film editing machine similar to the machines that were used to edit films in the analog era, before digital editing was available. These machines had several switches used to rewind, fast-forward, and pause the film while viewing it, and the game recommends using a controller with analog sticks as the preferred control method, to mimic the feeling of using one of these vintage editing machines for an extra layer of immersion.

You start with just one piece of footage available to you, and as you’re viewing any piece of footage, you can pause it at any time and use an on-screen cursor to “connect” any visual element you see in the film to another piece of film by clicking on it. Images that are similar or related to a frame from another piece of footage are highlighted with an eye symbol, making it easy to know what might lead you to your next new piece of film. This feels a little bit like a point-and-click adventure game on the surface, as you look for items, symbols, faces, or anything else in the visual language that might lead to you more clues. As you start to unlock more footage, it all gets laid out on a grid where you can easily jump back and forth between any of the scenes you’ve already seen before and sort them by several different methods.

As you start digging through the footage, you’ll notice that much of it is behind-the-scenes or ancillary footage like rehearsals or even talk show appearances regarding the films, and there are also small snippets of behind-the-scenes just before and after each scene that was filmed, since this is all previously unedited footage. This is where you’ll start to get some clues about what may have happened to the actress herself, as you dig into the tiny book-ends of the footage.

After a short time of playing, it sinks in that the sheer production value and layers of writing that went into the video footage included here are staggering, not to mention that the writers, actors, and crew had to write, plan and film three movies worth of footage plus a meta-narrative structure just to create this experience. It’s something that hasn’t been matched with this level of fidelity, authenticity, and weight in the video game format before.

Barlow’s cinematic eye and talent as a visual director is on display here more than ever before, with gorgeously-framed and composed shots abounding, and with each piece of footage perfectly matching the time frame it took place in, from the sets and costume designs down to the lighting techniques and even the type of film and camera that’s used; everything feels hauntingly accurate to the period.

As you piece together certain ideas or theories and see more footage, you’ll start to feel like a documentary filmmaker who’s creating their masterwork in real-time, and the immersion takes on a new level that hasn’t been matched, even in Barlow’s previous games. While the other games may be somewhat similar in format, in being non-linear investigative thriller narratives that are explored through a “digital detective” framework, they pale in comparison to what Immortality has achieved.

Immortality demonstrates a big leap forward, not only in the creative freedom and power expressed through the work but also in the game design being much more accessible, letting you sink into the story more effortlessly.

If you’ve looked at screenshots or footage from the game, you might be wondering, aside from the first movie from the 1960s being based on an old gothic horror tale, what does Immortality actually have to do with horror?

This is a question that is entirely part of the plan with Immortality, as almost everything you see and hear on the surface of the game and the footage within has a seemingly normal and typical “mysterious Hollywood disappearance” vibe to it, but once you start peeling back the layers of what’s contained here, you’ll see the horror elements start to unfold slowly.

The way this will happen is that eventually, while scanning through the footage, you’ll notice strange noises or even slightly out-of-place visual elements in the film, and will generally just keep moving forward and viewing more scenes without taking much notice. At a certain point, you’ll end up manipulating something a certain way to where these strange and subversive images become more clear as you scan them in different ways.

As these images become more clear, you’ll start to find “hidden” footage that was injected into the film itself, and that has very little context upon first discovering it, but as you work to make these subverted images become clear, you’ll also start to notice some haunting and unsettling background music start to flood the soundtrack, telling you that you may be on to something deeper.

Eventually, these uncovered images will start to connect the dots between certain events or images you’ve previously seen, and a much deeper level of story beneath the surface starts to bubble up slowly, along with increasingly disturbing imagery and uncanny vibes.

The story, on all its levels, explores such a vast and deep array of themes, including things like the nature of humanity and human ambition, the place of artists and art in a commercialized society, the dark underbelly of the Hollywood system/dream, the price of chasing celebrity and fame, the effect of traumatic events on human beings, feminism and the treatment of women throughout human history, existential dread, the duality of “acting” as a human trait and artistic trait, the parasitic nature of human relationships, the nature of various art mediums as a whole, sexual abuse, exploration of organized religion and its control on society, suicide, and so many more that I can’t list without including spoilers.

This narrative weaves together so many strong influences from so many different sources into such a cohesive, intelligent, and compelling package, while also being mind-bending, esoteric, and deeply haunting in a way that only a select few pieces of media have ever achieved. The meta-narrative, featuring a mix of real-life events and the settings these fictional worlds take place in is a masterful work of blurring the lines between art and reality; another one of the strongest traits in a great piece of fiction.

As a word of warning, Immortality will certainly not be for everyone. It’s a very slow burn that rewards patience and determination from the player to keep delving down the subsequent rabbit holes of lore and information, with no action scenes or 3D movement of any kind, but a much more psychological and thoughtful narrative that evokes the slowly-emerging horror of classic literature and mythos under the surface of what appears to be an entirely different game at the start. The experience requires an appreciation of the medium of video games, but also of the art forms that precede and inform video games, to put all the pieces together and realize what an important step this game is for the format, as the game seeks to merge or blend the most dominant art forms of the past with the most dominant art form in today’s world.

Subversion of expectations is heavily implemented here: another strong key to what makes the best art, and this piece of art demands much from its viewer, even beyond the surface-level piecing together of a timeline of events, but also the piecing together of cryptic or poetic pieces of dialogue or imagery that are not clearly explained by any sort of narrator or clear-cut exposition. On a higher level, even the name of the game on the title screen will change after the first time you start editing and then exit back into the menu. Like many of the best works of art before it, it requires a level of intellectual investment from the audience to unearth its true value and depth. A certain level of foregoing many “gamer” expectations and preconceived notions of what video games are is necessary to get the most out of the experience.

Speaking of the subversion of expectations, after about 8-10 hours of playing and discovering what was presented as an “ending” of sorts, there was a credit roll to signify that you’ve reached some sort of end to the story. However, as the credits roll, you’ll notice some strange things going on in the background and some hints that something else is going on even as the credits keep scrolling. It turned out that I had only discovered around half of the footage and story that the game had to offer, and knew very little about what was truly going on in the grander scheme, and it subsequently launched into a whole other layer of storytelling and mystery that just got even stronger than anything before the credits.

Thankfully, the interface and the framework that Immortality uses to tell its story is a far more sleek and user-friendly interface than the two similar games that came before it (Her Story & Telling Lies.) Not only is this interface more streamlined and easy to navigate, but the pacing and flow of information this system presents are far more compelling, satisfying, and well-balanced than its predecessors, leaving very little time without being able to discover new information, which is the key to keeping a good mystery story moving forward.

There’s a certain thrill to every aspect of the game experience here, from the constant thought process or deduction of figuring out where the next piece of the puzzle will appear to the subtle trial-and-error manipulation of the film to expose the hidden secrets underneath, to finally piecing together more bits of story that lead towards a more definitive understanding of the whole; the entire experience is exhilarating for anyone with an inquisitive mind.

Beyond experiencing it alone, the game can be experienced simultaneously with real-life friends to partake in the game, using the minds and experiences of multiple people to deduct your next steps or contemplate the meanings of what you see, giving it yet another level of joy if you have any friends or family to experience this with, and if you choose to do so. As the creators have stated, there is no wrong way to enjoy the game, short of giving up before you’ve found enough information to answer the questions you have.

After spending around 15 hours with the game to uncover all of the footage and connect all the dots of the story, I can easily say that Immortality is one of the strongest pieces of fiction created in the medium of video games and an experience that will stick with me for years to come. Hopefully, everyone else can get as much out of this game as I did, and the industry will be a better place when more gamers can embrace a game with such an unconventional and masterful presentation as this one. Immortality is available today on PC and the Xbox Series consoles, and is included with the Game Pass service, so don’t deny yourself this experience if you have a platform to play it on.

As a fun nod to one of the game’s very strong influences, I’d like to close this with a short series of questions or things to think about that you may ponder as you play the game, which might help you connect a few far-reaching dots that may not be apparent on the surface, similar to the “clues to understanding” David Lynch’s Mullholland Drive that were included on the original home video release of the film in 2002.

The creator of Immortality provided some similar ideas in the press material, and this is my spoiler-free take on the idea.

- What really happened to Carl Greenwood near the end of filming “Minsky”?

- Why was there such a large time gap between “Minsky” and “Two Of Everything”?

- The story that you (as the player) are discovering/editing in 2022 is referred to as a “fourth film” of sorts, with the theme of “Concordance” on the official website.

- Is there anything strange about the appearance of John or Marissa in 1999 versus 1970?

- It’s mentioned that Marissa starred in some commercials before being cast for “Ambrosio”.

- Is time a linear and finite concept in every story and in the mind of every character?

- How does art have such a strong ability to influence an audience, even hundreds of years after it was created?

- Mirrors are often a gateway to introspection in fiction.

- Who were the directors of each of Marissa’s three films and why was each film never released?

- Who else auditioned for “Ambrosio” and what became of them?

(10 / 10)

(10 / 10)

The Holy Grail

(10 / 10)

(10 / 10)Rely on Horror Review Score Guide

A review code for PC was provided by the developer.

IDOLxISxDEAD

IDOLxISxDEAD