When video games first arrived in arcades, they were designed with a business model, meant to make as much money as possible. Developers knew that to get the most coins from the gross hands of children, their games needed to be difficult. The harder the game, the more money would be required to get that one extra life upon death. Once home consoles were released, this line of thinking continued. It took a few years for games to move away from their obsession with high difficulty and focus on better pacing and accessibility. Developers eventually realized that continued punishment wasn’t really fun or rewarding for the player. Some developers have taken the design mechanics of older games — difficulty and all — and have created genuinely gratifying experiences. Others have used those same design mechanics and decided to focus on punishing the player instead. Unfortunately, this uncomfortable space is where Dream Alone resides.

Developed by WarSaw Games, Dream Alone is a 2-D platformer that takes clear inspiration from other titles such as Limbo and Inside. The game follows a young boy living in a town that has been struck by a mysterious illness. One by one, his neighbors have fallen into a coma, and now the young boy’s family has suffered the same fate. All seems hopeless until he finds out that Lady Death has the powers to stop the disease and cure those afflicted by it. Grasping at the smallest amount of hope, the young boy sets out to find Lady Death and help his family and his neighbors. One would think that a quick visit to Lady Death would be relatively easy, but Dream Alone is quick to reassure the player that this won’t be the case. Deadly monsters and brutal traps inhabit a world where everything and anything is out to kill him. The setting and story of Dream Alone are incredibly oppressive. From the game’s early moments, the player realizes this world is one of danger and misery. Though it isn’t groundbreaking and doesn’t offer anything we haven’t seen before; it doesn’t need to be. The story acts as a great launching point for these emotions and provides enough incentive for the player to continue on their quest.

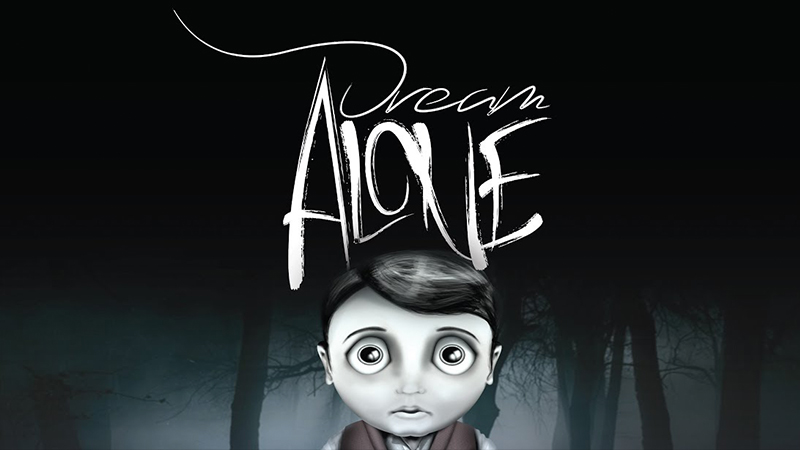

Another aspect of the game that significantly adds to the bleak tone is the art style. Dream Alone takes inspiration from films of the 1920s and 30s. The entire game is in black and white and incorporates a film grain effect that hammers home its inspirations. One odd decision, however, is a strangely implemented dimming mechanic. On a regular basis, the screen will dim to black, completely obscuring the player’s view. Though I can understand why the developers made this aesthetic decision, I cannot fathom why it made it through testing and into the final game. The issue with this will become clear once I discuss the gameplay of Dream Alone, but considering this game is a platformer, you can likely guess why this would be a problem.

The gameplay was also designed to add to the somber tone of the game. Dream Alone does not mess around. Players are tasked with completing several platforming challenges such as jumping over enemies and avoiding traps, while occasionally solving some puzzles — pretty standard platformer motions. Where Dream Alone sets out to differentiate itself from other platforming titles is its difficulty. This game is hard, but not in a way that feels rewarding. It is more like the game is continually trying to cause the player as much frustration as possible. Each challenge, enemy, and puzzle seems as though it was designed to make the player experience intentionally unenjoyable. Everything in the game kills the player in one hit; everything leads to a game over. Unlike other games with similar difficulty, Dream Alone combines all of these aspects in a way that makes the player want to put the game down and never touch it again.

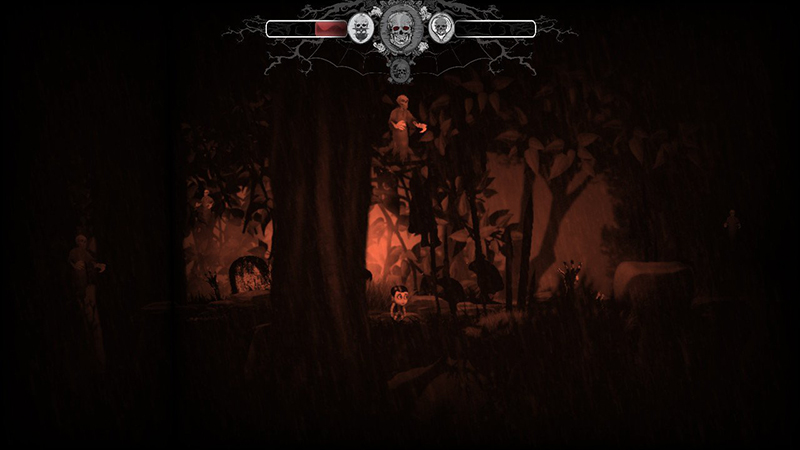

The designs of the enemies found in Dream Alone are pretty impressive. Some look as though they were ripped out of Lovecraftian stories, while the central plot and setting of the game feel like something coaxed out of tales told by candlelight. Though the enemies are aesthetically pleasing, their mechanics vacillate between frustrating and utterly pointless. Enemies come in two varieties: small and large. While their designs might vary- some are merely spider-like while others are grotesque- they all operate in the same way. Foes walk backward and forwards, and all the player has to do to progress is to jump over them. Seems simple, right? The problem lies with how many enemies appear on screen at once. Usually, enemies will spawn in groups of 2-5. The issues with enemy encounters lie with a floaty jump function, instant-death, and no discernable movement pattern. When there are more than two enemies on the screen, trying to find a gap between enemies is exceptionally annoying. The flawed jump mechanic makes these encounters frustrating and leads to many, many deaths. Perhaps, had these enemies been designed in a way that the player could examine their patterns, overcoming these challenges might feel rewarding. Instead, the game falls into a constant string of trial and error punctuated by the game over screen.

The game’s art design only exacerbates these issues. Since Dream Alone‘s visuals are entirely black and white, the enemies blend into the background. Objects in the foreground also hide enemies at times, causing them to materialize from behind trees or rocks at the last second. Enemies are just too difficult to distinguish from the background; combined with the constant fade-to-black screen effect, they might as well be invisible. In a platformer where everything kills the player in one hit, this leads to many moments where the art design of the game feels like it’s working against the player.

The other defect players must contend with is the wide variety of traps. These include spiked balls and blades swinging from the ceiling, pits with spikes in them, and walls that will crush the player. My personal favorites are rocks or spikes that fall out of the sky, giving the player absolutely no time to react before dying. Flicking a switch temporarily stops some of these traps, but most must be avoided by crossing your fingers and running past. You’ll need the luck because the traps require precision down to the exact pixel to prevent death. Remember, the player character can’t move very fast, and their jump is very floaty. Traps are designed with these movement limitations in mind but barely give the player any breathing room. There were several moments where I thought I had made it past a trap, only to die because the trap was close enough to me for the game to decide otherwise. In Dream Alone, it always feels like progress is up to chance — die, rinse and repeat until completed. This gameplay loop takes away any sense of a rewarding challenge and devolves into anger and monotony.

Dream Alone does try something interesting with the inclusion of special abilities. These include the ability to switch to an alternate dimension, place a clone of the player which can be used to hold switches in place, and finally, creating a light to illuminate the darker levels. I found the alternate dimension ability the most interesting. When triggered, the world changes: the screen turns red, silhouettes of people hanging from trees decorate the background, and everything feels more terrifying. This abrupt change adds to the onerous nature of the game. In regards to gameplay, triggering this ability can alter the landscape. Platforms may appear, or obstacles may disappear, with some puzzles designed around this mechanic.

A significant issue that affects all of these except the clone ability is that they are attached to a meter that depletes quite quickly. Once consumed, players must refill the meter by finding potions scattered throughout the levels. These potions tend to appear near where the player will need to use an ability to progress. This doesn’t mean, though, that the game always supplies enough potions to progress. Since meter drains quite quickly, if the player hesitates for even a second, they may not have enough time to complete a challenge or avoid death. Players are unable to test obstacles because of these incredibly strict time limits. The hurdles within the puzzles are enough to make them a challenge, but tying most abilities a meter that depletes at such a fast rate feels like the game desperately wants to screw over the player.

Potions don’t respawn and rarely are there enough to fill the meter. So, failure to solve an ability-tied puzzle means the only recourse is to die. This isn’t fun; it’s boring. The fact that potions are even near puzzles makes me question exactly why these abilities have a meter. Instead, why not allow the player to trigger their abilities whenever they want? Completely remove the monotony of trying to refill the meter and enable the player to experiment with their abilities, which could make puzzles more interesting. Developers wouldn’t need to put up signs telling the player, “Hey, you need to use an ability here.” Everything would feel more streamlined and less mechanical. The sad thing is that in any other game when I get a new ability, I feel rewarded because they offer something new and exciting to experiment with. When Dream Alone gives me a new ability, I mutter to myself, “What nonsense am I going to have to deal with now?” This question is usually answered with, “A lot of nonsense.”

All of these issues culminate when the player realizes how inconsistent the checkpoint system is. When you die, the checkpoint system may feel generous enough to spawn you just before you met your demise. Most of the time, however, it will screw the player. Setbacks related to the trial-and-error nature of the game tend to happen during extended sections. Players make a fair amount of progress, dodge the annoying enemies and precision traps, only to die because a rock dropped from above and killed them. All of that progress is now lost, and all the player can do is sigh and muster up the motivation to try again. The most frustrating design choices could at least be endured, but inconsistent checkpoints actively force players to experience them repeatedly.

I had high hopes for Dream Alone. Aesthetically, it is everything I want in a video game. The depressive nature of an Edgar Allen Poe novel combined with a 2-D platformer seemed like a dream come true. That dream turned into a nightmare less than 30 minutes after I started the game. I enjoy challenging games, but they need to find the right balance between difficulty and fairness. Not once during my time with Dream Alone did I feel any satisfaction when conquering its terrain. The difficulty, coupled with its enemies, art style, traps, and abilities, made my time with Dream Alone full of frustration and confusion.

The developers wanted to make a tough-as-nails 2-D platformer, and they did precisely that. In that respect, I praise them on the execution of their intent. It’s just a shame that intention doesn’t create fun or rewarding player experiences. Every aspect of Dream Alone feels designed to make players want to put the game down and walk away, which is something I needed to do on several occasions. Some people may find enjoyment in this style of game, but not me. Dream Alone did provide me with something I had never known was possible; I was unaware until now that a video game could hate me.

(3.5 / 10)

(3.5 / 10)

Poor

(3.5 / 10)

(3.5 / 10)Rely on Horror Review Score Guide

Nintendo Switch review code was provided by the developer.

ThomasHartDuff

ThomasHartDuff