Last month, I released the first installment in a series of articles that delved into the intersections of mental health and horror gaming. Part 1 highlighted games that, in my opinion, excellently centered empathy, prioritized lived experience, and crafted humanizing stories that complicated and subverted historic narratives surrounding mental illness and madness.

Part 2 will criticize games that, regrettably, perpetuate damaging stereotypes and narratives rooted in stigma. So let’s examine some examples of games that woefully miss the mark.

Opening Wounds

How games handle themes of violence, self-harm, and trauma poses potential threats to players’ well-being, especially when games present them in graphic detail and brutality, without exposing or expanding upon them within the plot. This can cause some players to feel triggered or morally wounded.

How games handle themes of violence, self-harm, and trauma poses potential threats to players’ well-being, especially when games present them in graphic detail and brutality, without exposing or expanding upon them within the plot. This can cause some players to feel triggered or morally wounded.

Take, for instance, Martha Is Dead, a game released in 2022. It approaches subjects such as trauma, abuse, violence, gaslighting, war, and dissociative identity disorder (DID) from a somewhat passive perspective, lacking in specific details and offering only broad strokes. The story relegates these traumas to the background without delving into their intricacies. While some games have explored the impact of war on soldiers, the effect on civilians often goes overlooked (a common flaw among other games discussed in Part 1 and beyond). DID, as a diagnosis, typically arises from profound childhood trauma, but the game oversimplifies the development of alter egos or multiple personalities as coping mechanisms—a tired trope often seen in Hollywood and entertainment media, sadly replicated here.

Although the blurring of the first-person environment in-game effectively creates an ambiguous sense of reality, reminiscent of derealization and other trauma responses, the game ultimately feels gratuitous in its portrayal of disturbing subject matter, offering little resolution or contextualization for the experiences it depicts.

The questionable actions of the protagonist, Torque, in 2004’s The Suffering take precedence over the game’s mental health undertones. The gameplay’s unique Morality Meter creates a distinction between Torque’s mental state and his decision-making, but this distinction becomes increasingly unclear as the game progresses. Rather than emphasizing Torque’s mentality, violent acts are portrayed as reflections of his moral judgment, yet the game fails to explicitly convey this lesson. These actions visibly transform Torque’s physical appearance, gradually rendering him more demonic with each act of violence he commits, thereby highlighting the consequences of his choices. However, it is important to note that engaging in violence does not inherently make someone demonic.

This portrayal echoes the problematic conflation of mental illness with being “evil” in popular culture. Ultimately, The Suffering falls short in distinguishing the player’s choices from Torque’s motivations, resulting in little more than a brutality simulator. The gaming industry as a whole struggles to capture the complexities of violence, although games like Tell Me Why (previously discussed) make commendable attempts to do so.

Exploiting the Madhouse

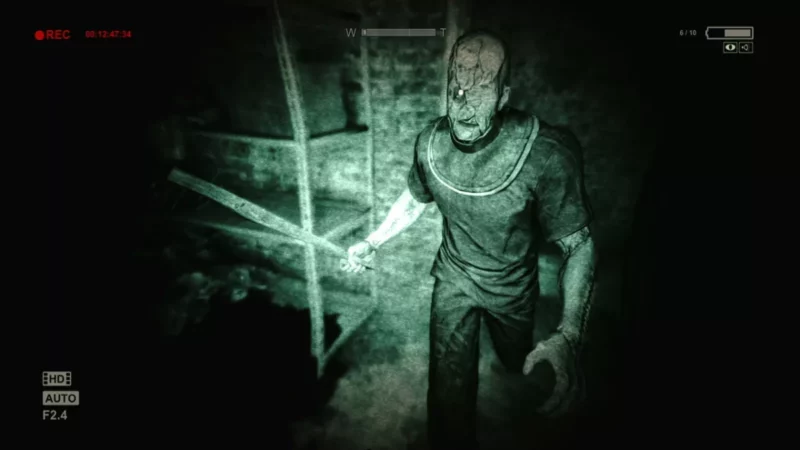

As discussed in Part 1, many classic horror titles feature hospital environments that have become synonymous with horror. In the 2013 game Outlast, the main character Miles actively investigates the derelict and decrepit Mount Massive Asylum, which has been completely overrun by patients (referred to as “Variants” in the game’s lore). These Variants are portrayed as derogatory caricatures of individuals with mental illnesses, reduced to violent and deranged non-player characters (NPCs) who roam the halls engaging in self-mutilation, talking to themselves, and posing threats to the player character.

As discussed in Part 1, many classic horror titles feature hospital environments that have become synonymous with horror. In the 2013 game Outlast, the main character Miles actively investigates the derelict and decrepit Mount Massive Asylum, which has been completely overrun by patients (referred to as “Variants” in the game’s lore). These Variants are portrayed as derogatory caricatures of individuals with mental illnesses, reduced to violent and deranged non-player characters (NPCs) who roam the halls engaging in self-mutilation, talking to themselves, and posing threats to the player character.

Stereotypical imagery and activities associated with mental illness are showcased simply to ramp up the scares. Later, the game reveals that the use of dream therapy on traumatized patients serves as the catalyst for the Walrider, the most dangerous and powerful force in the game. All of these elements firmly cement Outlast in tired, overused, and frankly boring stereotypes. The notion that trauma somehow grants a person supernatural powers perpetuates a harmful concept present in various forms of entertainment media. Outside of the use of the night vision camera and a focus on non-combat, there’s very little originality here.

The game’s successor, Outlast 2 (2017), and even more so the recently released The Outlast Trials (2023) explicitly incorporate undertones of insanity into the plot. In the 2023 game, the Sinyala Facility, which serves as the lobby for players (referred to as “Reagents” in-game), features architecture reminiscent of psychiatric hospitals, complete with a nurse’s station, medication counter, and dayroom. This design choice proves intriguing for players who, like myself, may have experienced hospitalization, whether voluntary or involuntary.

While aligned with the game’s overall lore, the location also resembles a prison, evoking a strong sensation of entrapment for the player. In terms of gameplay, an enemy known as “The Pusher” sprays the protagonist with a noxious gas, inducing a state of “psychosis” that restricts the player’s ability to navigate the environment. These mechanics, along with the Insanity Meter, add an interesting dynamic to the gameplay. However, it is crucial to note that the concepts of depleting one’s sanity and inducing psychosis are entirely inaccurate.

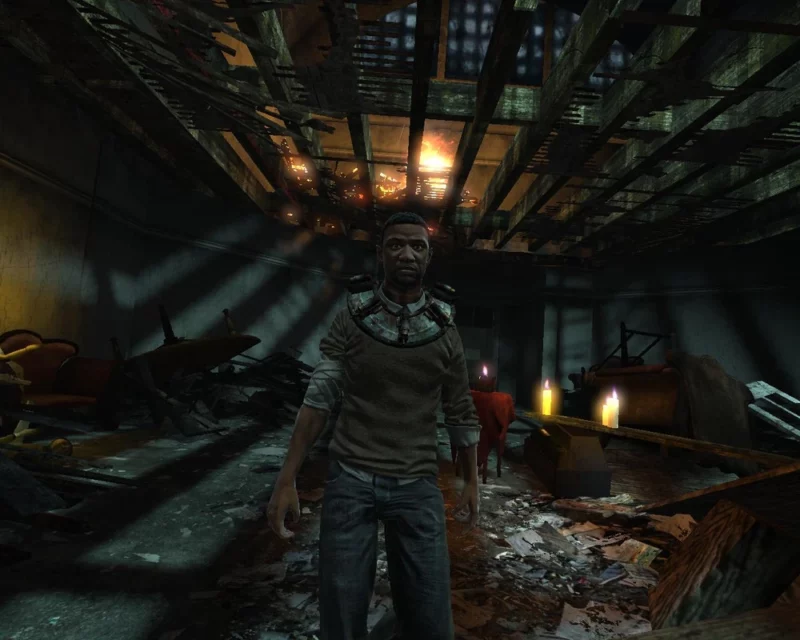

In 2014’s The Evil Within, the main character Sebastian receives a summons to investigate a gruesome mass killing at Beacon Mental Hospital. As the story unfolds, we discover that the hospital, like many others in the horror genre, serves as the site of experiments conducted on patients by the game’s main antagonist, Ruvik. He seeks to merge minds together with his own.

While the plot offers a unique exploration of the intertwining of traumatic lived experiences and memory, the portrayal of the character Leslie as a “blank slate” for mind transfer carries derogatory undertones towards individuals with specific cognitive needs. In fact, the significance of the lived experience is nearly entirely disregarded in favor of a revenge-driven plot, rendering the mental hospital setting more of an homage to the genre rather than a meaningful exploration.

Not Doing the Work

Horror games frequently exhibit this pattern, as seen in 2009’s Saw: The Video Game, where Whitehurst Insane Asylum serves as the primary location for David Tapp’s trial but could easily be substituted with any other abandoned location. Numerous examples exist where mental hospitals merely act as a backdrop for player terror.

Horror games frequently exhibit this pattern, as seen in 2009’s Saw: The Video Game, where Whitehurst Insane Asylum serves as the primary location for David Tapp’s trial but could easily be substituted with any other abandoned location. Numerous examples exist where mental hospitals merely act as a backdrop for player terror.

Here’s a non-exhaustive list: 2021’s Tormented Souls (Winterlake), 2009’s F.E.A.R. 2: Project Origin (Wade Hospital), 2018’s Call of Cthulhu (Riverside Institution), 2010’s Alan Wake (Cauldron Lake Lodge), 2015’s Until Dawn and 2018’s The Inpatient (Blackwood Sanatorium), 2011’s Dead Space 2 (Titan Memorial Medical Center), 2007’s Silent Hill: Origins (Cedar Grove Sanitarium), 2009’s Batman: Arkham Asylum (you get the idea).

In 2007’s Dementium: The Ward and 2010’s Dementium II, the majority of the gameplay unfolds within psychiatric hospitals. The main focus revolves around exploring the hospital environment, gathering clues, and engaging in battles with monstrously transformed patients. It is important to note that the Nintendo DS version of the first game faced opposition from the Japanese Association of Psychiatric Hospitals due to the brutality of its gameplay and its depiction of patients.

While the sequel deviates from this, the game resorts to the cliché of amnesia (another well-worn media trope) and the pursuit of “the truth” as justification for harming patients. It completely erases their humanity and replaces it instead with poor enemy design.

A Fate Worse Than Death

In my opinion, one of the worst examples in the genre is Cry of Fear, where harm and mental distress play significant roles in its five endings. This 2012 game follows the protagonist Simon, who gets hit by a car at the beginning of the game and must navigate a city infested with monsters to find his way home. As the game progresses, we explicitly discover that the Simon we have been controlling is a fictionalized version created by the actual Simon, who turned to writing as a coping mechanism after becoming wheelchair-bound from the car accident.

In my opinion, one of the worst examples in the genre is Cry of Fear, where harm and mental distress play significant roles in its five endings. This 2012 game follows the protagonist Simon, who gets hit by a car at the beginning of the game and must navigate a city infested with monsters to find his way home. As the game progresses, we explicitly discover that the Simon we have been controlling is a fictionalized version created by the actual Simon, who turned to writing as a coping mechanism after becoming wheelchair-bound from the car accident.

The game could have been unique if it stopped there. Instead, the five possible endings all involve violent outcomes for the characters, with Simon either committing murder, suicide, or a combination of both against himself, his therapist, and/or his love interest. These actions stem from his inability to cope with the reality of his new disability. Unfortunately, the game merely reinforces the damaging trope that death is preferable to living with a disability. As a neurodivergent individual and a member of the Disability Justice community, I vehemently disagree with this horrendous premise.

Lastly, I would like to draw attention to one studio that has greatly concerned me with its use of mental health. MadMind, the studio responsible for the graphic 2018 game Agony and its 2021 sequel Succubus, has positioned itself as a pioneer in pushing boundaries within the genre, shifting from merely implied horror to explicit depictions of gory mayhem. Two upcoming titles from the studio, Paranoid, and Tormentor, have specifically given me significant cause for concern.

Paranoid places you in control of Patrick, an isolated man who grapples with the trauma of losing his entire family in a tragedy. After years of self-imposed seclusion, Patrick feels compelled to break free from his isolation when his missing sister suddenly announces a visit, despite having disappeared a decade ago. Little else is known about this title, scheduled for release later in 2023. My hope is that the game delves deeper into the perils and consequences of isolation, presenting a compelling narrative centered around Patrick, rather than resorting to the use of psychosis as a means to justify the horror.

The United States is facing an epidemic of loneliness, and a game that sheds light on this distressing reality can be both empowering and necessary. Conversely, a game that portrays psychosis as an existence worse than death will only contribute to an already overcrowded and inaccurate landscape of media that has unfairly targeted schizophrenia. Schizophrenia (often conflated with DID) has been unjustly used as a scapegoat in horror media for far too long.

I am significantly more wary of the other game, Tormentor. The game is lauded as a “torture simulator,” and gameplay videos released so far showcase a cat-and-mouse style of gameplay, where players sneak up on intended victims and brutally slaughter them with gruesome, graphic detail. Did I mention that most of these victims are naked? Yeah, gratuitous.

I am significantly more wary of the other game, Tormentor. The game is lauded as a “torture simulator,” and gameplay videos released so far showcase a cat-and-mouse style of gameplay, where players sneak up on intended victims and brutally slaughter them with gruesome, graphic detail. Did I mention that most of these victims are naked? Yeah, gratuitous.

Setting aside concerns about what a “torture simulator” actually entails, the Steam listing for the game actively encourages players to “fight against a developing mental illness” by obtaining drugs to “keep your mind sober”. This is achieved through online interactions with fans by the unnamed Tormentor who broadcasts their killings for increased viewership. The more views garnered, the more drugs and funds the player acquires to procure new torture devices. The premise itself is not only in poor taste but also utterly absurd. The notion of torturing unsuspecting victims as a means of averting mental health crises is so outrageously illogical that it would be comical if it were not deeply disturbing.

In conclusion, video games have the potential to be a powerful locus of public dialogue and education around the realities of mental health and madness. There are many examples to celebrate, and many more to critique and challenge. As a mental health advocate, psychiatric survivor, and mad artist, I cannot wait to experience more games that take a sincere look at the true horrors of the history of mental health treatment and normalize narratives that not only normalize mental health, but that uplift the joy and celebrate the power of neurodivergence in all its many forms.

In conclusion, video games have the potential to serve as influential platforms for public dialogue and education concerning the realities of mental health and madness. There are numerous examples worthy of celebration, as well as numerous others that require critique and contextualization.

As a mental health advocate, psychiatric survivor, and mad artist, I eagerly anticipate encountering more games that genuinely examine the disturbing horrors associated with the history of mental health treatment, while also promoting narratives that not only normalize mental health but also embrace the joy and celebrate neurodiversity in all its many forms.

TheSvenBo

TheSvenBo