In 1999, the original Silent Hill was released and gamers across the world were introduced to protagonist Harry Mason, a father desperately searching for his lost daughter in the titular fog-bound town. His search would take him to the very heart of the otherworld and back, and all throughout that journey, Harry’s was the voice that accompanied players as they navigated the twisted world of the game. His unique delivery set the tone for the series and became the standard for every other Silent Hill performance to come.

For many, SH2 is considered the epitome of the series, but for me, the original Silent Hill will always be my favorite, and that’s in no small part due to Harry’s character and performance. Harry had a singular goal: to find his daughter. He was a grounded, relatable everyman in a video game landscape dominated by exaggerated military commandos and super-powered heroes. Playing as an ordinary guy in extraordinary circumstances was compelling and a dynamic that really resonated with me. While some may have felt he was a little on the passive side, I’ve always felt that quality was an essential part of the first game. Harry was a vessel for the story and his dreamy delivery and minimalist performance perfectly suited the nightmarish world he found himself in. Rather than take away from the experience, it enhanced and added to it by creating its own unique language and tone. I liken the style to the performances in a David Lynch film; odd, off-center, but appropriate and purposeful, both to the story and characters of their respective worlds. I have personally wanted to speak with the voice actor who played Harry for many years. No one had ever heard his story or even knew who he really was. I considered it the holy grail of SH interviews.

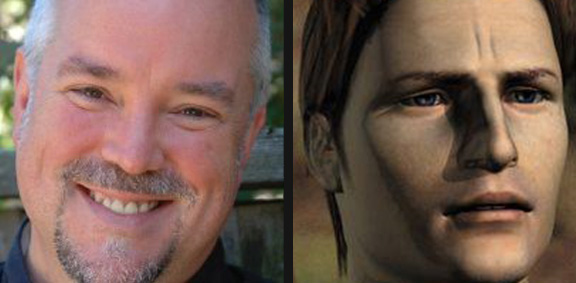

For years there was a great deal of debate and speculation about who actually voiced Harry, since the only name listed in the credits was simply “Michael G.” Everyone from videogame voice actor Michael Gough (Resident Evil 4, Gears of War) to film actor Michael Gough (who played Alfred in the Tim Burton Batman films) were mentioned as possible contenders. An erroneous interview with voice actor Gough, published in an Oct. 2007 issue of Electronic Gaming Monthly and crediting him with the role, did little to stop the confusion. In May of 2009 a fan contacted voice actor Gough, who confirmed he was not the Michael G. listed in the credits of SH1 and requested the credit be taken off his IMDB page. Since then, there has been little new information concerning the true identity of the mysterious and elusive “Michael G.”

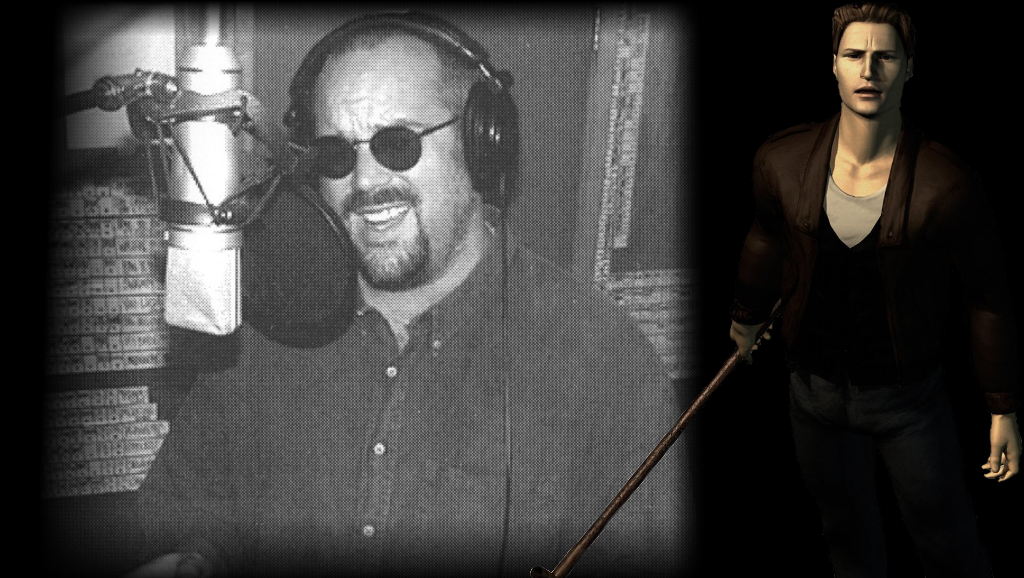

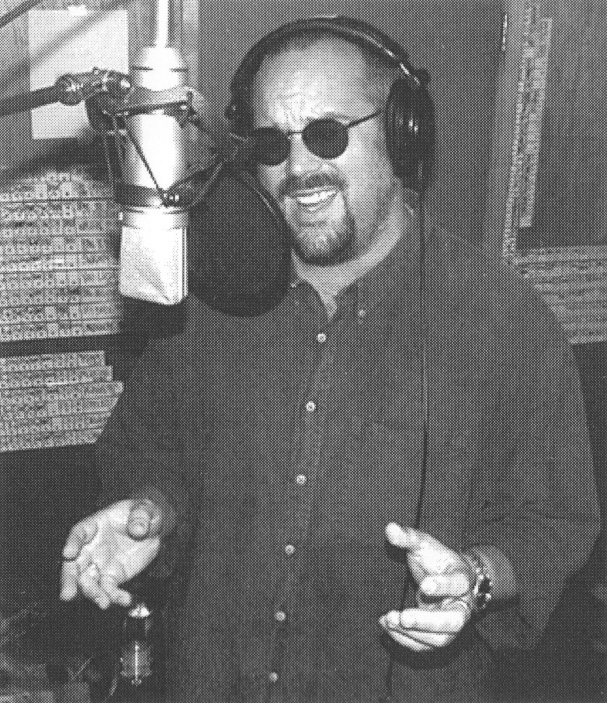

After years of back and forth and speaking with multiple sources confirming his identity, the true Michael G. has finally been found! His full name is Michael Guinn (pronounced “GWEN”). I was fortunate enough to get the chance to talk with him extensively about his life and career. It was an absolute pleasure and honor to hear all about his amazing experiences. In addition to being a great talent, he was also an incredibly warm, genial guy. He’s a man who has led a very interesting life and in his first public interview ever, is now able to tell his story.

SPOILER WARNING: This article contains spoilers for Silent Hill 1 and 3.

William: Hi Michael! First of all, thanks for accepting my request for an interview.

Michael: You’re very welcome! I deeply appreciate your persistence and patience. When you contacted me, I thought wow, I have to get organized and we have to do this.

William: Is this your first public interview, regarding Silent Hill?

Michael: Yes it is, actually. It’s my first interview, so you scored, dude!

William: Tell us a little about yourself.

Michael: Well, I was born and raised in Texas. I moved to Santa Barbara in Southern-Central California when I was sixteen and finished high school there. I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life, but I knew I enjoyed acting. The first school I went to was the University of California at Irvine, where they had a really good acting program. I lived a hundred yards away from the theater, which they left unlocked at night. I would walk in there at midnight and do monologues and soliloquies (usually sober) and I just loved it. I really thrived on living the theater life, and acting for that one year at UC Irvine was really everything to me. I hope all sorts of artists today have a chance to really study their craft, because I think there’s this thing that goes on in music and in acting where there’s some pride where people say, “Well, I haven’t had any training whatsoever and I’m so good” But if you’re that good and you add training to it, you’ll be great. Really. I’m a big believer in training and I really loved, loved my training. After my freshman year, I got asked to front a pop/rhythm and blues band. I was nineteen. I was thrilled to be so young and took a year off school, singing my butt off. I put myself through school by being a recording artist. I also worked part time on campus, but the big money came from being in the studio and recording vocals during those years. I didn’t know that that was going to come in handy later on, but I was very comfortable in studios and working with engineers and all of that as a result.

After that break, I decided to move to the University of California, Santa Barbara where I transferred to their acting department. The acting department at UC Irvine was just outstanding and cutting edge, but at UCSB they were still reading Stanislavsky like he was still alive. It was like being in a psychology department and you just came from the very latest psychological techniques and maybe at least they’re talking about Jung, and you transfer departments and they only know Freud. After a year of that, I knew I needed to do something else. I met this East Indian professor there, Raghavan Iyer, who was lecturing in Political Science and that led me to start getting interested in life abroad. So, I transferred over, completed the next four years in that department and graduated with a degree in international relations. After that, I realized the one thing missing from my life was that I had never lived abroad. I felt very provincial. By the time I left school, I owed what seemed like to me an onerous amount of money (about $7500). I read this book called Jobs in Japan and how I could pay off my student loans. I had paid for everything, but I still owed payment on some government loans. I wanted to pay it off as quickly as possible. I found out you could go to Japan and even after you’d paid for your expensive apartment and plane ticket, you could still make really good money. So I did that. Like most people who go to Japan, I had to teach English for the first couple of years to get my visa to legally work there.

William: How did you get into videogame voice over work?

Michael: It’s kind of an interesting thing, because I was involved in so many of the very early videogames, many of which even predate consoles like PlayStation, Wii, Xbox and things like that. Then, I was right there at the cusp, when all of a sudden PlayStation all the others started coming out. All of a sudden people who weren’t in arcades were actually hearing my voice, and it was interesting. It brought a certain depth and a different kind of audience. That time in Japan, ’87 to ’97, was during the boom times in Tokyo, where there were HUGE, multimillion dollar budgets for T.V. commercials, for games, for anything. They just kinda had money running everywhere, through the advertising industry, their entertainment industries, and they were still very much enamored with the United States and Americans and English. So any native speaker of English they just assumed was a trained actor or musician if they said they were. I was, but there were plenty of people there who were basically just teachers who went over there, who got a lot of work doing voiceover work, as well. I was one of the rare people there who had actually trained for that through acting schools and theater and radio.

I had only been in Tokyo maybe 4 months and it turned out that my upstairs neighbor was a girl from L.A. who was singing jingles in Tokyo. I said, “Oh, I’m a session singer too and I have a background in theater.” And she said, “Give me your tape and I’ll have a listen.” Then the next day, I came back home and there was this huge note on my door and it said, “Oh my gosh, I need another set of your demo tapes!!! There’s this huge commercial for Sony Walkman and they want to audition you!!” A day later they brought me in to what I thought was going to be the audition and it was the most beautiful, biggest studio by, like, a factor of three or four, that I had ever walked into in my life. They throw the score in front of me, and it finally dawns on me – this is not an audition! I’m standing there and there’s all the Sony executives there. Apparently, the commercial that I did was the advent of the Sony Walkman wired ear buds. It felt like a scene in a movie, it just was surreal. So, I sang it and I walked out, and they were shaking my hand and said they’d like to talk about doing an album. That was my very first commercial in Japan. It was an amazing experience. Every musician or every actor always wonders what’s gonna be their little moment. For me that was an amazing introduction to being a recording artist in Japan and ultimately began to lead towards radio and voiceover work and a lot of videogaming and things like that.

William: What was your first voice over job? What did you think of the videogame voice over industry?

Michael: In the very early days a lot of the bread-and-butter jobs were often recording extremely boring stuff for English language learning tapes. I was saying things like, “If I buy two, will you discount it? If I buy three, will you discount it?” I’d be running through all kinds of things like that. Not particularly exciting, but you give it your all. As time went by, it was more fun. The commercial stuff was way more fun.

I was a Sony recording artist and that exposed me to a lot of directors. I got to experiment with different character voices. Usually they didn’t use any sort of weird filer on my voice to create them, I created them myself. That opened up this whole character voice thing for me, and more and more different producers, especially videogame producers, started listening to that. I had a better demo reel of different character voices. The videogame stuff must have taken off in the early nineties. Maybe ’92 or ’93 was when I first started getting a lot of that work. They were interesting because a lot of times, in the early days, the Japanese didn’t really know what they were doing in English. If you went in as a voice talent of any kind, you often had to rewrite things and say, “No, we would probably not say such and such.” So, you would have to go in and help rewrite scripts and things like that. I was kind of the Swiss Army Knife of session singers and voiceover work because I could approximate so many different sounds and styles. I always loved doing character voices and dialects my whole life growing up and never thought I’d get paid to do so. It was so fun being there and getting offers to do voiceover work, and then finding out that I was actually marketable! I couldn’t believe it. It really pushed me to the edge of what I conceived I could possibly do. I loved that about Tokyo during those times. It was fun to try anything. I had the most dreamlike existence of just doing what I loved and paying all of my bills with my voice, which for me was the definition of success.

William: How did you get cast in the role of Harry Mason in Silent Hill?

Michael: Up until Silent Hill, all the premises in videogames were pretty much the same. So, it was really interesting when I went in and had the meeting with Harry Inaba, the director, about Silent Hill because he said this was going to be different. He said, “We’re going to do a horror videogame. It’s truly going to be scary, with lots of different possibilities and ways you can go. We’re going to create a mood in this thing.” The point was, it was going to be different. Now, I had heard that many, many times before. But, this time, it really was different! It was pretty scary, as many other gamers realized as they played it. I remember listening to some of the music as well. It was frightening. The uniqueness of this job was in the genre they were working in. Konami was very proud of that. It was that kind of crazy time in Tokyo, where there was creativity spilling out everywhere.

William: What did you think of Harry as a character? How did you prepare for the role?

Michael: I seem to vaguely recall that the character of Harry in Silent Hill, from my perspective, was probably really scared the whole time. But, what he was feeling was annoyance and anger and an incredible kind of powerlessness about what the hell happened to his daughter. I mostly thought about what it would be like to be afraid and angry at the same time. I personally hate fear. I can’t stay in a fearful place. I don’t know if that’s a typical thing for men or just my family of origin, or what. I often will go to anger or annoyance to get out of that place of being afraid.

In all fairness, we didn’t get a lot of prep time. I’m pretty good at cold reading things. That’s just something I’ve been lucky about. It’s never gonna be quite as good as when you really spend time and research and go over the lines so that they fly off the page more easily, but that wasn’t an option for so many of the jobs I did. I liked that challenge.

William: In preparation for this interview, I went back and listened to your work in the game. It still holds up. It’s such a genuine, sincere performance.

Michael: Wow, that’s wonderful to hear. Thank you!

William: What was your reaction to the script? Were you shown the full script or just your individual parts?

Michael: If I’m being totally honest, at that stage it probably seemed like another script. Harry Inaba said it was going to be different, and I liked Harry a lot and I trusted Harry a lot, but I had heard “different” many, many times, many, many jobs. After you’ve done about twenty or thirty of these types of jobs, you feel like you’ve got the rhythm, you know how they go. Japan has a fairly homogeneous culture, so a lot of the expectations are similar. There’s not as much nuance, because they’re dealing with a language that is not their own, that’s not native. I think probably I didn’t think too much of it. I didn’t think poorly of it, I’m just saying I didn’t go, “Wow, this is an amazing script! This is gonna be great! I’m going to be doing an interview in twenty years with somebody and it’s gonna be a fan favorite!” Never occurred to me. Again, not because it was bad because it wasn’t. It was obviously good. It just never entered my mind.

I think I had the full script. It was 60 pages, which was pretty rare. It was one of the longer scripts I ever worked with. Pretty darn good for a videogame (back in the 90’s)!

William: How were you directed in your recording sessions? How long did the process take?

Michael: I don’t think I ever worked with Konami without Harry Inaba directing. He was pretty much their hot director at that time. He was one of the coolest, nicest people I met in the entire ten plus years I was in the voice over industry in Tokyo. I teased him, because the lead character I was going to play was also named Harry. He swore that he didn’t choose that. He probably met the client and they liked his name, but I don’t know if they used it because his name was Harry or not. Working together on a project, whatever it was, was effortless compared to a lot of the other directors I worked with. They were not truly bilingual and didn’t quite get a sense of what we were doing, so it was a little more work. Harry was unusually bicultural. He just had a certain ease about him and he truly understood the nuances of the language better than easily 95% of all the directors I worked with. So, he became a friend, as well as a colleague and a guy who would hire me whenever he had something for me. Just a delightful guy. He just had that magic touch. All my memories of him are very fond.

It was an interesting process. It was a huge script. I bet Harry would know for sure, but I’m pretty sure we recorded this over a short week’s time, probably three or four days, maybe longer, which is unusual. Most of my jobs we were able to knock out in a long afternoon, or sometimes you go into the evening. The voice over work rarely went late into the night.

William: Thessaly Lerner (voice actress of Lisa Garland) said that the voice director on Silent Hill was the same guy who was the lead character and that he had to do the voice because the guy who was supposed to be that character got another voiceover job that paid better for that day. Can you confirm any of this?

Michael: That doesn’t sound right. I never directed. On a lot of my jobs I would end up helping out fellow actors or things like that, but no, I never sat in the director’s booth. Harry Inaba was there from start to finish. We weren’t always all in the studio at the same time. I had so many lines, so I was there a lot, but I don’t believe there was any other actor cast for Harry Mason other than me. I never heard any story about that. I’d be surprised if anyone other than Harry Inaba did any of the directing. That’s kind of a weird story, because I didn’t see anybody job-hopping in Tokyo. That’s almost like career suicide to say you’re gonna do a job and then go do another job. That’s pretty rare.

William: Maybe she was just a little confused.

Michael: Maybe. What she is describing sounds really dramatic and I would remember something like that. I certainly never did anything like that. I was pretty careful not to overstep my bounds. There was no hopping in the director’s seat. That just wasn’t done. Maybe there’s some interesting, mysterious backstory I don’t know about.

William: Silent Hill is a series known for its dark, psychological themes. How did you deal with the subject matter and was it ever something you found objectionable or challenging to deal with?

Michael: That’s a good question. It didn’t feel particularly gratuitous. It seemed to be wedded to a storyline. I’m not a huge fan of the horror genre, but that being said, I think Silent Hill was probably pretty honest about what was happening. I love The Twilight Zone and Hitchcock, those types of things. The cheaper stuff just doesn’t appeal to me at all. That’s just pure gore, with no story to go with it. It’s just pornography in that sense. I don’t feel like Silent Hill did that.

William: Did you enjoy working with Konami? Did you think the Japanese writers and developers did a good job creating a western story with English-speaking characters?

Michael: I loved working with Konami because, for me, working with Konami was all about Harry Inaba. Maybe I had some jobs with them without him directing, but because Harry was so bilingual and so bicultural, the communication between us was great. I worked with well over 150 different music and voice over directors during the ten years I was there and they varied all across the scale. I never felt frustrated with Harry. I didn’t have to enunciate or choose my words carefully. He followed me. It felt very collaborative and I trusted him. We had great respect for each other.

Yeah, I think so, in the end. I think it still has a really alien feel to it that probably works for the game. There’s a very interesting thing about Japan, which I kept trying to describe to people, and then finally that amazing Bill Murray film came out, Lost in Translation, directed by Sofia Coppola. Living and working in Japan had with it this strange sense of alienation that Lost in Translation captured so beautifully. In it, Bill Murray plays a famous U.S. personality brought over to Japan to do some really dumb commercials (which really happens). There’s a scene where he’s finally alone in his very small luxury hotel room. Most of the lights are off, I think just a bathroom light is on, and he sits on the bed. The shot just has him sitting on the bed silently. It’s a 30-40 second shot and that’s all it is. In that shot you get that sense of alienation, of being a foreigner, being a non-Japanese person living in Japan. To some degree, foreigners, particularly Americans, come over and begin to get a sense of what it must be like to be a famous person, because everybody stares at you, constantly. That’s what it feels like being in Japan and being very obviously not-Japanese. And so I think Silent Hill has this odd sense of alienation in it. The Japanese producers, directors, writers, programmers and everybody who worked on this game, tried to imitate a western feeling, a western game, and they did, but there are all these other elements that create this sense of odd alienation. They took these western ideas and pushed it through the filter of Japanese culture. What comes out is not Japanese and it’s not western, but it’s very interesting. All of that works to make the game and atmosphere more creepy.

William: Did you have any scenes with other actors when you were doing the voices at the same time?

Michael: Yeah, I think so. I have a vague memory of the studio we were in. Like most of the voice over studios, the one that we used for Silent Hill wasn’t particularly glamorous. It didn’t need to be. Voice over studios don’t need the huge ceilings for acoustics, space and lighting, so they’re much more innocuous and quiet. Everyone chain-smoked all the time too, which is another interesting aspect. I smoked during that time. You could either be miserable because there’s tobacco in the studio all the time, or you could smoke. So, I just started smoking cigarettes, so it didn’t bother me as much! I gladly quit when I came back to the States.

William: It is my understanding that due to the technological limitations of the original PlayStation there were pauses in between the lines of dialogue, due to the fact that the game had to load the sound files individually each time. How did the effect of this limitation differ from how you performed the dialogue live? Were you pleased with the end result?

Michael: The interesting thing about this script that proved a little bit odd or troublesome as we recorded it was that Harry said that I needed to leave a long, one second pause before and after each line. It was a very unusual style of recording. It was really hard to sound natural when I had to keep pausing. I much prefer to do things naturally. There’s an intensity about Harry (Mason) that was very hard to communicate with all the weird pauses I had to do. I was rather disappointed with what I heard in postproduction, but Harry (Inaba) said, “Oh, don’t worry, before they actually put it in the game they’ll close these gaps.” I imagine that it was mixed by Japanese engineers who didn’t speak English particularly well, and I don’t know what happened in the translation, whether or not they didn’t really tuck those in the way I understood or the way Harry explained. I think it’d be interesting to hear Harry’s point of view. I wonder if they did exactly what he said or they weren’t able to do exactly what he said. And so, that’s why there’s those weird, stilted pauses.

Having said that, what was cool about this game was that it wasn’t overacted. They didn’t want this big, wild, dramatic voice. They actually wanted a guy who was terrified and looking for his daughter and that motivation was the only thing that gave him the courage to walk through all these horrific things. As a parent now, boy I understand that. So, it was one of the more natural recordings, with a very unnatural style of recording.

William: Have you ever sat down and played Silent Hill yourself?

Michael: I never got to play Silent Hill. I saw a lot of the scenes as we recorded it and Harry Inaba talked through it, but I never played it.

William: Did you have any input on the story and/or translation at all? Did you know about the multiple endings?

Michael: I always pipe up if there’s something weird in the translation. We would always do that, because I didn’t want to be involved in saying something that no one would ever say or a word or pronunciation that sounded absolutely wrong. But for Silent Hill, I don’t remember marking anything in my script that was a change.

I was aware of the multiple endings, because we had to record all of those.

William: Were you aware that in one possible ending, the game cuts to a shot of Harry, unconscious and slumped down in the seat of his jeep, with a bleeding forehead and the car horn blaring – implying that he never survived the crash and that everything he had experienced was all in his head – a dream he was having as he lay dying?

Michael: I do recall that. I think I was told about that or I saw it.

William: That’s actually my favorite ending. It’s so compelling. It was the first one I got when my friend and I first played the game in college. I always imagined that right when the game cuts to that shot, in that moment, Harry dies.

Michael: That’s’ pretty cool. It’s very Twilight Zone-y, with the shock ending there.

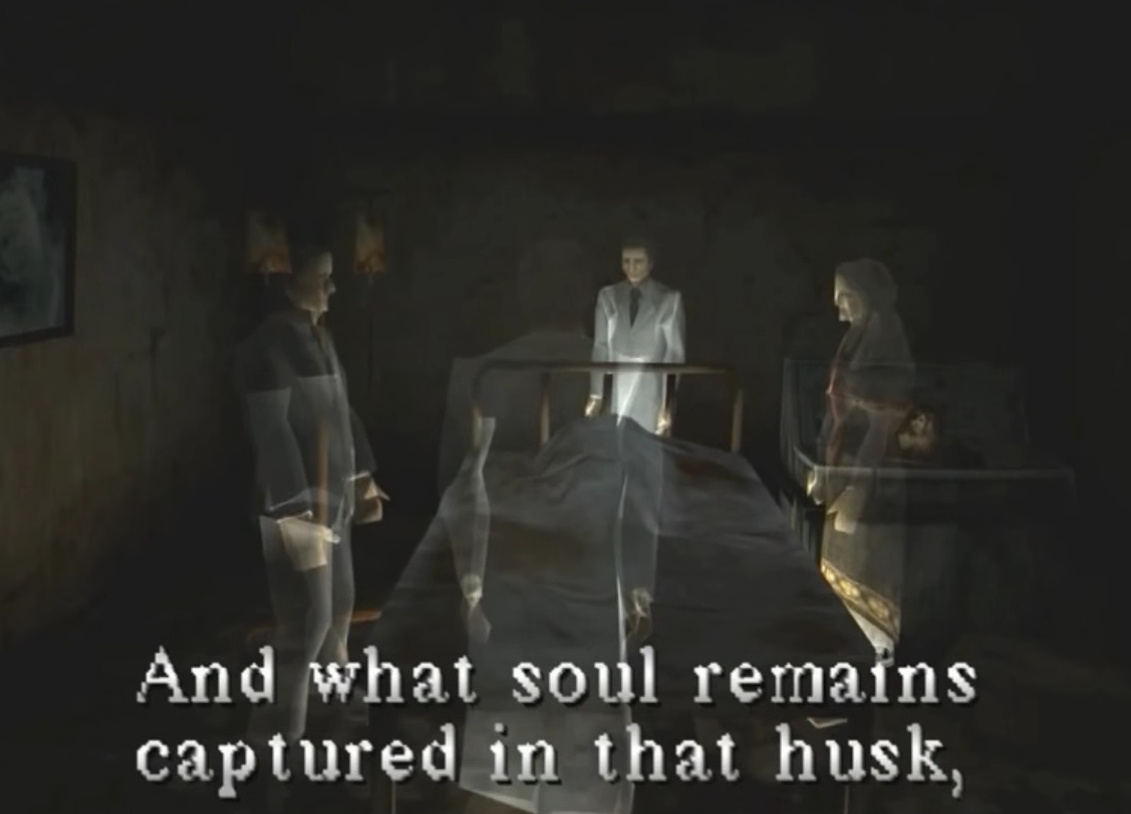

William: Did you know that Harry was actually officially killed off in the sequel to the first game, Silent Hill 3? How do you feel about that?

Michael: No, I didn’t know!

William: It’s actually a deeply poetic and touching scene. I was shocked when I first saw it. For me it underscored the fact that you can never really escape Silent Hill. It’s a tragic scene, which was done very tastefully.

Michael: Oh wow, that’s so fascinating. I don’t know if there was any good reason why I didn’t get involved with Silent Hill 2 and 3, other than I moved back to the states. Maybe they just assumed that I didn’t want to fly back to Tokyo to do it or they didn’t want to do it in L.A.

William: Besides voicing Harry in Silent Hill, do you recall if you voiced any other parts in the game? Towards the end there’s a scene with a group of four people talking around a bed, and it sounds like you’re one of the doctors. Do you remember voicing any other parts?

Michael: Yep, that sounds like me. I’m 98% sure that’s me doing one of the extra voices. I very rarely only did one voice.

William: Did you have any idea how big the series had become?

Michael: Oh no, not at all. You never know what’s going to take off and what’s going to track. I kinda walked away from the industry when I moved back to Santa Barbara. It’s so interesting. I would meet game programmers or whatever and I’d go, “Oh, yeah, I used to do voiceovers and things,” and they would say, “Well, have you done anything we would know?” and I said, “Well, I did Silent Hill,” and they would gasp! So I realized it was a thing, but it’s still kinda funny. It’s funny to be involved with something and have no idea that there’s this whole other thing that happens.

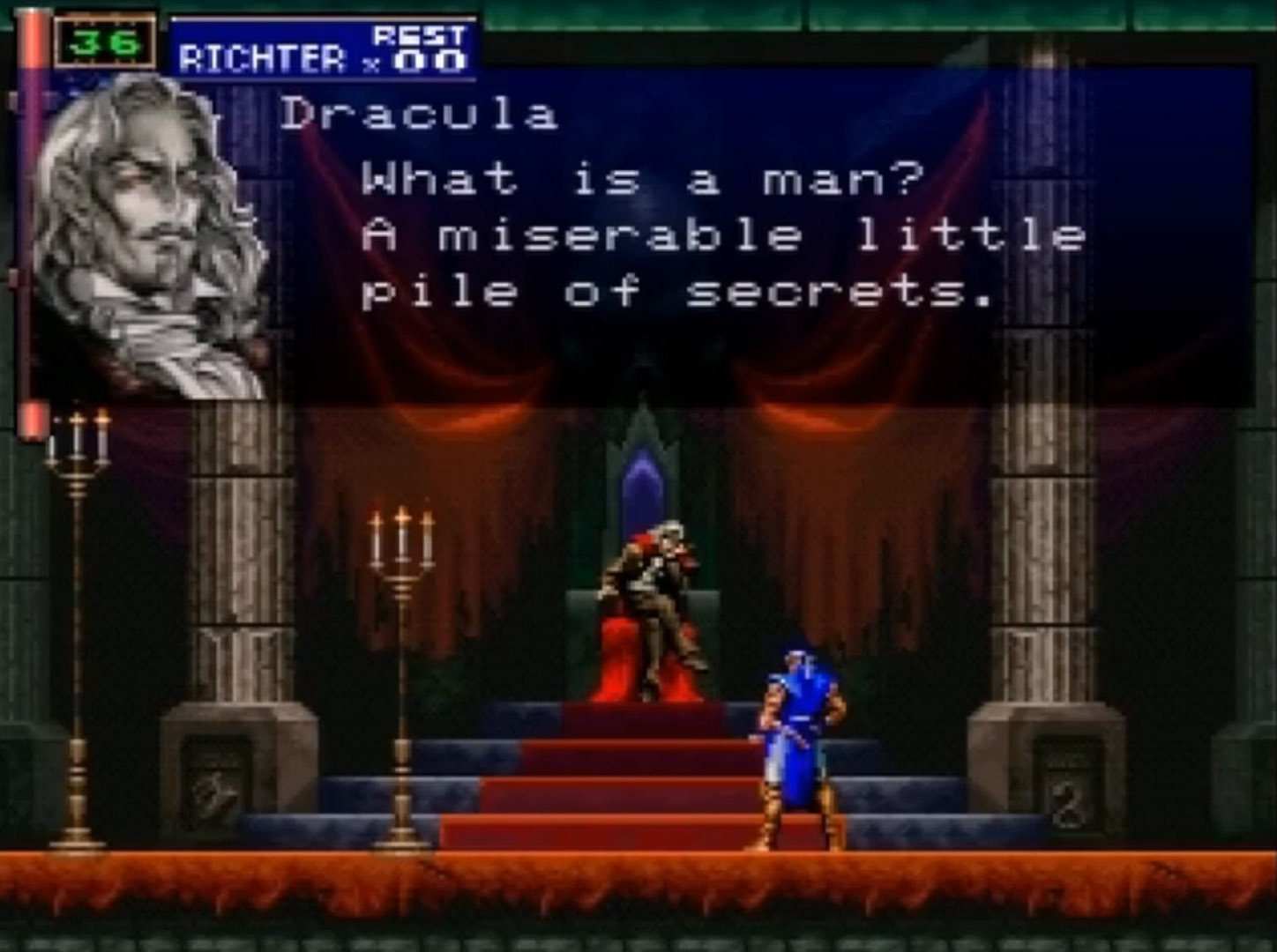

William: You also appeared in another Konami classic, Castlevania: Symphony of the Night (1997), voicing the character of Dracula. Can you give us any insight into what that job was like?

Michael: In the early days I had a lot of screaming jobs. I was good at the death knell, apparently. I think I got the part of Dracula only because they liked the way I screamed and died. I had a wicked, evil sound or something like that. I’m pretty sure that job was with Harry Inaba as well, because all of my memories of Konami were with Inaba-san. I landed back in the states in the summer of 1997, so it might’ve been one of the last games I did in Japan.

William: Was the decision to use a shortened version of your name in both games due to the fact that these voice over jobs were non-union? I’ve heard some actors choose to modify their credit, so as not to get into trouble with the unions. Can you comment?

Michael: No, not at all. It had nothing to do with union. When I signed a record contract with CBS Sony, they felt like my last name “Guinn” was going to be too hard for the Japanese to say. They wanted it to be catchy and easy. You think that a lot of thought goes into these things, but I was literally in that meeting with my management and Sony, and I said, “When we were kids, we just used to use our initial for our last name.” And everybody just lit up. They were like, “Oh, it’s GREAT! Michael G. It’s PERFECT!” Unfortunately, Kenny G released an album about three months after that meeting, but in Japan they never made the association. During my voiceover work I was always known as Michael G. That was primarily because the Japanese couldn’t pronounce my last name. So, no, it had nothing to do with unions or hiding or anything like that. There was no union there. Your union was only as good as your management was. After that, I heard they were making foreign artists sign contracts. I don’t know if that was true, that’s just what I heard.

Here’s an interesting story about the Michael G. thing. I didn’t even know that I had an IMDB profile, and they were linking Michael G. to a guy by the name of Michael Gough. The irony is, I knew him! He was actually one of the teaching assistants at the University of California Santa Barbara’s acting department. We didn’t know each other well, but I knew him. He is probably 5 or 8 years older than me, something like that. But I had to get in touch with him, I can’t recall why, to let him know, because he was kind of annoyed that people kept thinking he was Michael G. I don’t know if that fascinates people or not!

William: Other than Silent Hill and Castlevania, what are some of the other voice over roles you’ve done?

Michael: Do you know the claymation character Pingu? I believe it’s a Swiss-created character. They brought it over to Japan and there was this really interesting audition call. They wanted us to make up a language for Pingu! It was just the kind of impossible challenge that I loved. So, I made up this whole voice and just did all these kinda funny little sounds, in relationship to how the little claymation guy’s mouth was moving and what he was doing. And I got the job! They loved it. That was kind of typical of some of the wild and fun and crazy, creative ideas that a lot of the Japanese directors would have at that time. Being different in Japan is very radical and they were really trying to buck the culture.

I also did a lot of Namco games, including Time Crisis (as Sherudo Garo, the knife throwing villain). Another one was a game called Ridge Racer. I was the announcer. I had a rough script and I ad-libbed a lot of stuff. It was the first game to ship with the PlayStation in the states, which was really interesting. Most of the stuff I was doing at that point would never really leave Japan. Apparently, they liked me enough to package that game with the very first PlayStation and used it on an American TV commercial, which was kind of wild!

William: Wow, I didn’t realize you were the announcer! That voice was pretty popular in the west. That’s crazy to find out that you actually did that!

Michael: That was me, yeah. In all fairness, I think it was big because it was the only free game they shipped with the PlayStation. I still have an old, beat up copy of the game. I never got to play it, though!

William: Would you ever consider returning to do voiceovers for videogames?

Michael: I’ve always thought it would be fun to get back into voice over work. And I certainly know people. Just stuff here locally in town could be fun. I think with the right people. I don’t think that I would be attracted to doing it just for the money. I would want to do it for the right reasons. You know, just in talking to you, I would love to go back and do a Silent Hill project with everybody who was involved in the original. That would be a delight! Maybe I could help with the writing! It’s funny, when I talk about it, I get a little nostalgic.

William: In addition to being a talented voice over artist, you’re also an accomplished musician and incredibly talented writer. Can you describe some of the things that drive you creatively?

Michael: Could you just say that one more time? (Laughs) I’m kidding. Well, I love to laugh. Anything that makes me laugh is good. I love humor. I think it’s one of the high arts. For my birthday last month, my wife took me on a surprise trip to L.A. and we went to The Comedy Store. I had never been. It was a very interesting journey to go there and see where Richard Pryor, Robin Williams, Garry Shandling and so many of the greats got their start in stand up. In my writing I try to capture something that makes people laugh, but also has poignancy. In my best attempt as a writer, if I can make people laugh, cry and think, I feel like I will have succeeded. Particularly these days, when we’re exposed to so much news and information, be it on TV, social media or just the feed that’s hitting our email. We’re being overwhelmed by all the bad news in the world and all the partisan politics in America. I think more than ever, we have to find things that make us laugh, especially humor that doesn’t make you laugh at the expense of others. People who can make other people laugh really should be some of the most highly respected people in our society, and they’re usually not. I would like my writing to bring levity to people’s lives. If a book I write makes people laugh, and makes people think and reflect, I will feel like, mission accomplished, like I’ve done something really valuable. I think we all really, really need to laugh.

William: The original Silent Hill will be celebrating its 20th anniversary next year in 2019. It’s a series that has defined for so many what horror is, not just in videogames, but in any medium. Do you have anything you’d like to say to all the fans out there who have enjoyed your work over the years?

Michael: Oh gosh, well, thank you! I mean, how could you not say thank you for something like that. I’m truly honored. I give tons of credit to Harry Inaba and the people behind him at Konami who arranged everything. I’m thrilled. I’m really touched. I would love to see the entire game, I think that would be interesting.

William: What’s next for you Michael?

Michael: I’ve started writing the great American “novel.” It’s actually a memoir about my youth in Texas. I have a couple other books queued up, as well. I’ve never written a book, an actual piece of prose. I’ve gotten very intrigued by that and learning how to be a writer. I started an Apple technology company to pay all the bills and I sold that a couple years ago to get back to writing. I’m super happy to be not in the tech world anymore and back to doing creative stuff now. In fact, I am going to be starting grad school to get a Masters degree in writing. I’m thrilled about this. If anyone is going into any creative field, be it writing, music, acting or dance, I would encourage them to get an education in that and not be that person who says, “Oh, yeah, I never took a lesson in my life and I’m good.” Like I said earlier, if you’re good without a lesson, imagine how amazing you would be if you actually studied your craft. Imagine how much more your performance, your ability to create, can grow because you actually trained. Get away from the vanity of saying, “I never studied.” I was so glad that I had years of stage work behind me before I got my first voiceover job. All that work and training helps you. I really encourage all creative people to study. You can be so much more.

William: Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me. It truly was an honor!

Michael: You’re so welcome. You were super nice, William! Thanks a lot. It’s been really fun to talk about this!

Acknowledgements:

I would like to thank Retroplayer, AKA Denis Murphy for his invaluable help tracking Michael down and for providing a source of inspiration in his fantastic interview with Silent Hill 3 actress Heather Morris. You can follow him on Twitter @DrenMurph.

I would also like to thank my long-time collaborator and friend Tom Richards for providing some much-needed proofing on this article and creative suggestions.

About the Author: William is a freelance writer and illustrator living in South Carolina. When he’s not playing videogames and watching movies, he’s working on writing and illustrating his own fantasy series. Samples of his work can be seen on his art page.