‘Defining Horror’ is our new series that explores the creative minds behind the horror games that we love. Each entry in the series will share new aspects of the creative process, shining light on a developer’s ideas on what makes a quality horror experience, what elements are integral to a horror game, as well as what goes into effectively making an impact on the player. ‘Defining Horror’ is a series that aims to give gamers insight into what the horror genre means to those who have developed or are developing horror games.

Below you will find Sam Barlow’s definition of horror.

Name: Sam Barlow

Company: Climax Studios

Title: Game Director

Past Projects: Silent Hill: Origins, Silent Hill: Shattered Memories

Current Projects: Unannounced New IP for Next Gen

What I love most about horror are the mind games that kick in when we push beyond the ghost trains, those horror works that chiefly contain and communicate physical threat. Boo! Jump. Run for your life. Etc. Ghost Trains actually make you feel good when you’re finished. They’re jolts to the system that you can laugh about later. People walk out of ghost train movies and say “I had a good scare!”

Now, I like – sometimes love – ghost trains and find the brain chemistry fascinating – seeing how a receptive audience’s brains will actively work to maintain the illusion. The more scared they get, the harder their brain works — to the point where you throw spanners in the works (deliberately) and it makes the brain redouble its efforts. Abusing that mental apparatus that runs simulations on the world around you to help you predict and deal with deadly threats. Some great horror games hijack this apparatus. In the olden days it was easier. The sparse, abstract map of a text game like the LURKING HORROR needed your brain’s sim cycles just to exist. With later games such as THIEF it was up to the mechanics – missions that required you to traverse and re-traverse rooms and collections of rooms carefully – to commandeer that part of the brain. These games convinced your head they were real. The sense of being there, of reality has never been more heightened for me that in these games when my life depended on it. Amazing ghost trains.

BUT… the best horror for me is the stuff that goes beyond the sweaty fear, beyond just feeling real. The works that could kill you with an idea. Like a bear trap they ratchet when you brain goes in and when you try and pull out… it’s not pretty.

The last time I felt true dread in a movie theater was watching David Lynch’s INLAND EMPIRE. It terrified me with a scene involving a boom mike. And all that boom mike did was re-frame what I thought was happening. It made me feel like I was staring down a rabbit hole and might trip and fall in. I felt similarly reading Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves or Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy. A sense that the work has invaded my brain and I might not be able to kick it back out again. Stories about madness and reality that make you feel mad, that make you question your own reality.

Ultimately that’s the greatest of our human fears: is this real? Reptile brain fear is ‘Shit I might die!’ But when we’re safe in our caves at night, it’s ‘Is this real?’ that keeps us awake or haunts our dreams. We push beyond death (“I might die tomorrow!”) to something worse (“When I do die, this giant empty universe isn’t going to notice.”) The veil between our perception and the inky black, infinite reality is thin and vulnerable.

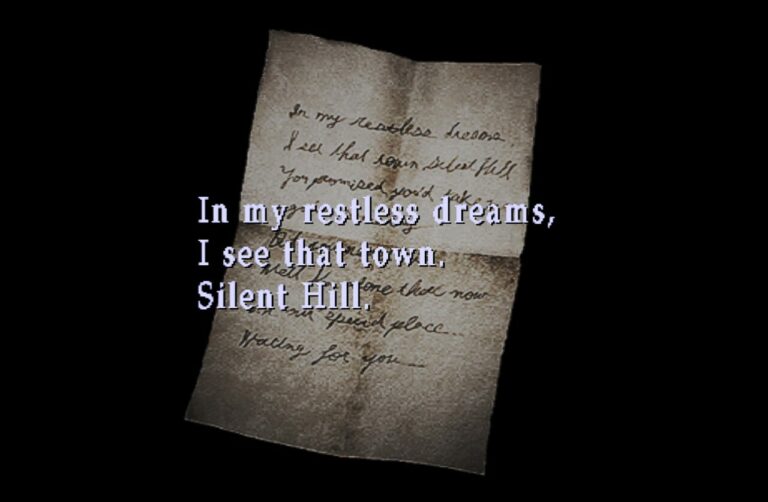

When horror starts laying on layers of perception and fucking with our brains this is the stuff that gets me excited. Step out of a ghost train and you’re done – ready to go grab some candy floss. But pull out of the bear trap of true horror — put down Shirley Jackson’s THE LOTTERY, step out of a screening of THE EXORCIST or finish SILENT HILL 2 – and this shit stays with you. You’ve been infected. Videogames are simulations, their worlds virtual — fake — realities. What better medium to peel back the veil?

When we made SILENT HILL: SHATTERED MEMORIES we wanted to fuck with your head, and not in the obvious ways (cheesy sanity effects, anyone?) We slowly wanted to make you feel like the game was watching you, that perhaps it was in your head. We wanted to make you uncomfortable by surrendering some personal information to our prick-of-a-psychiatrist Dr. K. We wanted to invade your intimate personal time – let you know we were watching. Videogames are places people go to act out, to do things they wouldn’t in real-life. But here, the game was watching – and taking notes. And in the final twist we wanted to hold your delusions up to the light. Show you this part of you you’d given up, this player character who had become enmeshed with some of yourself and see what it really was. Are you Harry Mason dreaming he is a butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming he is Harry Mason? (Before we’re accused of getting too nihilistic here, let’s note that after the phantasmagorical games were done with, Shattered Memories left us with something real – a real human being who was able to move on and perhaps live authentically for the first time).

Often videogames get so fixated with simulated reality they get confused and think that’s what they should aspire to. There’s a fallacy there – that reality is concrete and specific. But that’s not how we experience it. The masterful Gene Wolfe put it neatly, when asked why he was so fixated on unreliable narrators: “Real people really are unreliable narrators all the time, even if they try to be reliable narrators.” When I plug into a videogame I want it to fuck with my head. I think it’s probably healthy to want this.

There are two things I’m focused on at the moment with the team at Climax, both ongoing efforts. The first is the most straightforward. It’s breaking down interface intrusion. If there’s too much stuff between me and the game it’s very easy to say “it’s just a game” and contain it, partition it off. It makes it safe to handle. I’m not going to lose a part of myself to the sinister machinery if there’s safety glass in the way. This endeavor is easiest — it’s (just!) effort and clever thinking. Motion interfaces, touch interfaces, finding ways to remove gamey clutter – all useful stuff.

The second, the bit I’m kind of obsessed with is the manufacturing of a reality around the player. It’s not branching choice, it’s not conscious choice. It’s making the game world, game story, game period, fluid. Making the game work like a litmus paper that reconfigures itself to the player and to the way the player acts. This is about getting under the skin and into that good brain stuff without scaring the player off. Conscious thought is mediocre. Conscious choices are fun, but vanilla. We want a game that runs off the data the player is giving up without thinking about it (their ‘virtual body language’ is the term we use here). Many books and movies try to hold up a mirror to their audience, using projective psychology and symbols to allow people to make it personal. With the interactive technology that underpins all games, we can go further. A game designed not to flatter, empower or cheer the player’s mind. A game designed to fuck with the player’s mind. It’s healthy, I promise.

– Sam Barlow

cjmelendez_

cjmelendez_