I played The Music Machine earlier this year and was quite surprised by how much I liked it. Sole developer David Szymanski achieved a great story and well-developed characters in the game’s short runtime, with unconventional visuals and horror. Only upon completion did I realize that he too worked on another short narrative driven game, The Moon Sliver.

I got the chance to talk to David about his past horror games and his upcoming one, A Wolf in Autumn. Additionally we discuss his brand of horror and how to keep the genre fresh, themes of faith, and the progression of his development skills. Check all that out and more below!

Q: What kind of horror would you say you most enjoy / specialize in? The type you try to bring to the table?

In general I’m a lot more interested in atmosphere, narrative, and building a sense of paranoia than I am in outright horror, although that’s certainly not a hard and fast rule. I like focusing more on disturbing/creepy ideas than… you know, monsters jumping out and chasing you and that sort of stuff. It’s not that I’m opposed to those things, I just generally find the journey to them more interesting than the destination. And honestly, I usually find games that focus on those things to be merely unpleasant rather than engaging.

There’s this idea that horror games are judged solely by their ability to trick the player into a fight or flight response. Not only is that a very narrow view of things, but it’s also a very short-sighted view of things. As the technique and the technology of those types of games lose their luster, they cease to be effective. Doom and Quake used to terrify people. Half-life used to terrify people. Games like Amnesia and Outlast will eventually suffer the same fate, because technology will move on and their power to trick the player’s senses will diminish.

Stories are a lot more long-lasting. The Cask of Amontillado is still chilling. The Shadow Over Innsmouth, despite the overwrought prose, is still a very effective thriller. The principles of telling a good story don’t age, even if the language and techniques being used do.

Which is part of the reason my games focus on trying to tell an interesting story. I think it’s a deeper, longer-lasting approach to horror. And one that still hasn’t been developed on very much in gaming. I don’t know that I’m going to spark any sort of revolution with the tiny little games I make, but at least maybe I can fill a niche and maybe give other people some ideas.

Q: The Music Machine is a step up in terms of production value and scope over The Moon Sliver by a surprising degree. What led to such improvements? How have your skills as a developer evolved over the course of your games?

Well, I’ve certainly learned a lot about the Unity Engine, modeling, programming, etc over the course of each game. Fingerbones was the best-looking game I could make at that time, and A Wolf in Autumn is the best-looking game I can make now. And I hope another year will see me getting more competent. I’ve also learned a lot about game design since Fingerbones. Not just from getting feedback and trying to improve, but also from playing games with a critical eye. There are some flaws in my games I only noticed after seeing them in other peoples’ games. I didn’t realize just how important environmental interaction could be to immersion until I played A Machine for Pigs and found myself really missing it. So you see these really static environments in Fingerbones and The Moon Sliver, and suddenly everything has physics in The Music Machine.

I think there was actually a pretty big change in scope between Fingerbones and The Moon Sliver too. I mean, The Moon Sliver is probably at least 3 times the size of Fingerbones and there’s a lot more going on story-wise. However, one thing that changed between The Moon Sliver and The Music Machine is that I started doing game development full time. While working on The Moon Sliver, I was working a part time job and we (my wife and I) were struggling to pay our monthly bills. So if I’m perfectly honest, I was trying to get it out as fast as possible. I think I did some prototyping for The Music Machine before The Moon Sliver was Greenlit, but most of the development was done after The Moon Sliver was on Steam and had earned enough money for me to quit my job and for us to pay our bills. So the pace was a bit more relaxed, and I felt a little more freedom to spend time on things. And, I had more time to spend as well.

So to everyone who made that possible… I really can’t thank you enough!

Q: Any chance you’ll revisit The Moon Sliver someday a la Dear Esther?

Ok, this is going to sound stupid, but… I hadn’t actually considered it until now! I’ve had a few people ask me about redoing Fingerbones, and… well, I’m not sure that’s ever going to happen. But I wouldn’t be averse to remaking The Moon Sliver someday, maybe. If I felt like I had meaningful additions beyond just updating the visuals.

Q: How much bigger is A Wolf in Autumn compared to your last games?

It’s actually smaller! The Moon Sliver and The Music Machine were both products of very deliberately trying to do more than the last game. I didn’t start with a game idea, I started with the idea of doing another, bigger game. With A Wolf in Autumn, I just had a small-scale idea I wanted to try, and figured I could probably develop it in time for Halloween. In terms of real estate, it’s probably about the size of Fingerbones. I have a bit of a fascination with trying to make horror games in as small a space as possible. Actually, the original game was going to take place entirely in a single room. In terms of game length, it’s around an hour. However, it’s also more densely-packed than any of my previous games. There’s a lot more going on gameplay-wise, and a lot more “production value per square inch.” I’m hoping it will be a short but memorable experience that leaves players thinking (and replaying) for a long time afterward.

Q: Ties between A Moon Sliver and The Music Machine can be found if one looks hard enough, and popular theories on the Steam forums suggest the games are directly connected. Is there an overarching world you’re building?

In The Moon Sliver and The Music Machine? Yes. In all my games? No. Those two games are directly connected, but their world is maybe a little too fantastical for all the stories I want to tell. Fingerbones and A Wolf in Autumn aren’t part of the same world. That said, I might revisit it in the future. No promises, but it’s a possibility.

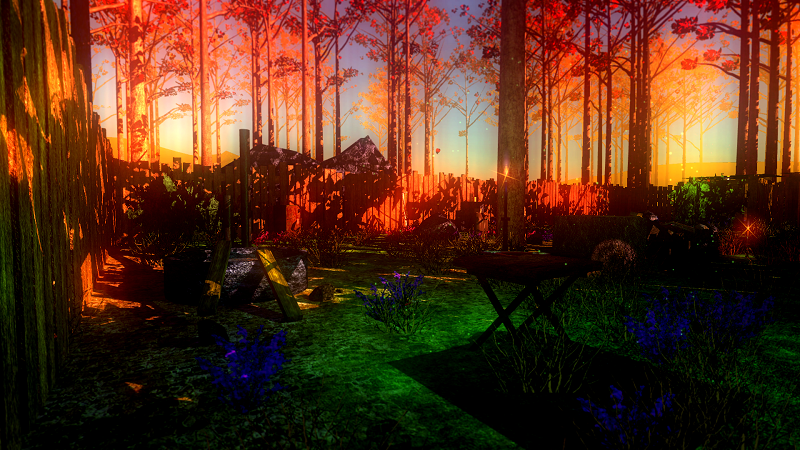

Q: You appear to have embraced vibrant visuals in both The Music Machine and the upcoming A Wolf in Autumn. Do you think vibrancy and a strong color palette lends itself to horror well?

I was actually tweeting about something related to this last night. The quirky indie exploration/horror/action/whatever game Betrayer by Black Powder Games features a really striking high contrast monochromatic artstyle (which influenced The Music Machine to a certain degree). And aside from looking super cool, the visuals really give it a sense of menace, even in brightly lit areas. It communicates the idea of a bright sunny day, while at the same time having a lot of darkness. And it perfectly captures the atmosphere of a wilderness forest: the contrast of beauty and a lurking sense of menace. Pretty trees and bright sunlight, but you might be eaten by a bear.

I think artstyle can contribute a LOT to atmosphere. I’m not sure I’d claim a vibrant, strong color palette SPECIFICALLY lends itself to horror well–in my case I just really love how a strong contrast between light and dark colors looks–but I think stylized visuals certainly lend themselves to horror well. Especially if they have an element of impressionism to them, forcing the player’s imagination to subconsciously fill in the blanks. And, of course, unique artstyles always age better than attempts at photorealism. Look at how crappy Call of Duty 4 looks nowadays. And look how good Unreal still looks even after all these years.

The artstyle for The Music Machine went through a lot of iterations. Eventually I settled on the monochromatic one, because I loved the nebulous atmosphere of decay, age, and discomfort it communicated. The main island especially. The exaggerated artstyle for A Wolf in Autumn has a narrative/subtext purpose, but it was also kind of me wanting to use a lot of colors after being so limited in The Music Machine.

Q: Both The Music Machine and The Moon Sliver feature narrative themes about faith. Misplaced faith, faith in false gods, etc. What informed / inspired this?

I guess my own Christian faith. I’ve dealt (and still deal) with a lot of questions and uncertainties. That’s kind of the underlying theme of The Moon Sliver: the horror of uncertainty and the yearning that maybe there’s ultimately something better than this. I don’t think it’s specifically a Christian game, because I think everyone struggles with these questions. It’s portraying life as I see it. A lot of confusion, but there’s this deep almost instinctive knowledge that something isn’t right, and there’s more than just this.

Wow, that all sounds really pretentious. The less artsy way to put it would be that I find the subject of religious uncertainty to be interesting, and wanted to explore it.

The Music Machine has some of those themes I suppose, but I wrote it more as being about childhood faith/innocence vs adult disillusionment. And the parts about faith kind of play into that.

Q: When it comes to writing characters, whether that be dialogue or notes, what’s your process in creating unique voices? I personally felt the characterizations were very good in both The Moon Sliver and The Music Machine; the dynamic between Haley and Quintin was especially enthralling.

Well… I’m still not convinced I know quite what I’m doing as far as character development goes, but a lot of people have commented that they liked the interactions between Haley and Quintin, so I guess I’m at least going in the right direction! I’m not sure there’s any specific method I use. After Fingerbones I wanted to focus more on characters rather than ideas. And I’ve been reaffirmed in this after playing SOMA and feeling dissatisfied with its narrative, which focused more on showing off ideas than on creating compelling characters and felt rather empty and self-indulgent as a result. Like I said, I learn as much (or more) from critically playing other games as I do from developing my own.

For The Moon Sliver, each character didn’t have much time to develop, so I tried to make their personalities pretty easy to understand, and make it easy to fill in blanks. I think they ended up being differentiated, which is a good thing, but apart from Abel they didn’t have much depth. So for The Music Machine, I figured longer game plus fewer characters. Again, I’m not sure there’s any specific method I can share… I just tried to walk a line between “strong” and “realistic.”

The thing is, I don’t think “realistic” characters actually work very well in short form fiction. Or rather, I don’t think they’re very memorable. If you’re like Faulkner and you’re writing a book that spends most of its time delving into their psyche, maybe… but in a two hour game, I think they need to be a little larger than life to actually be memorable. So Haley’s a bit overly weird, and Quintin’s a bit overly gruff, and I think that kind of makes up for the fact that you don’t spend very much time with them. If they acted like that for 12 hours it would feel too cartoony, but for 2 hours I think it works.

At the same time, I didn’t want them to just be archetypes that I pushed around. So I gave them both flaws and strengths, and I tried to make sure their actions were informed by their personalities, not just by where I wanted the plot to go. It’s a bit of a delicate balance. You want the story to play out a certain way, so you build the characters around that. But then, you want the characters to be natural, so you also build the plot around them.

I dunno. I think people are confusing and complex, often contradictory… so why would trying to “create” people out of thin air be simple? In general, I just tweaked and changed their personalities until they seemed interesting. Then, when writing the dialogue for objects you could examine, I did my best to communicate those personalities through what they said and (just as important I think) how they said it. And any time the plot or the characters didn’t seem to fit together, I just tweaked one or the other until they did.

No idea if I got it right.

You can find David Szymanski on Twitter @jefequeso. Check out his other upcoming game, The Grandfather, on IndieGoGo.