Samus Aran has Metroids, Space Pirates and other forms of alien life to blast her arm cannon at. Simon Belmont has Medusa Heads, Axe Armors and other creatures of the night to whip his Vampire Killer at. Samus enjoys exploring and being confined to alien worlds in the vastness of outer space. Simon Belmont enjoys invading Dracula’s castle to put an end to his reign. Dracula sits patiently waiting in the comfort of his throne room, Mother Brain rests within a glass tank. See where I’m going with this? If not, then, read on!

This past Saturday, August 6th, was quite an occasion. On that very day 25 years ago, players were introduced to the world of Metroid. Since then we’ve gotten some of the best gaming experiences of all time, most notably Super Metroid which is still seen as one of the finest titles ever developed. But that’s not all the Metroid series has done.

As any ‘vania fan can tell you, Metroid has been one very strong influence on a string of Castlevania games, starting with Castlevania II: Simon’s Quest on a lighter note and more notable in the highly praised classic, Symphony of the Night. Metroid’s influence on Castlevania has been so strong that a new genre was seemingly born: Metroidvania.

It’s not often you hear a majority of gamers cite Simon’s Quest as being the first title in the Metroidvania mold. And that’s most likely because of its notorious difficulty when it came to knowing where the hell you have to be and what you have to do to proceed on your quest to collect Dracula’s scattered remains. Even so, Simon’s Quest should be more appropriately referenced as the first non-linear ‘vania, because…it truly was.

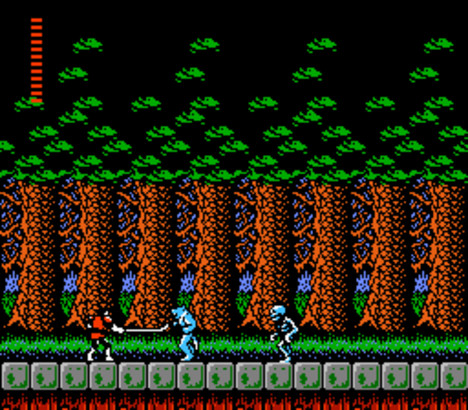

The original NES classic was a pure, linear, action-platformer affair. You would continuously push forward, taking on hordes of enemies and iconic bosses before ultimately ending up in Dracula’s throne room to whip the holy sh*t out of him, and thus send him back to his 100-year slumber. That was it, it was simply a sidescroller, and a masterful one at that.

Then came the infamous sequel; which was made even more infamous thanks to the Angry Video Game Nerd, but that’s another story.

Ah, yes. Where does on begin when talking about Castlevania II: Simon’s Quest? Well, I’ll start things off by saying that I absolutely loved the game, despite only beating it once. And I did so without the need of any guide (personal achievement unlocked!). And let me tell ya’: it was quite a challenge. Not only were enemies hard, for the most part, but now you were no longer thrown into one linear path; you were pit in quite a large world with towns and mansions interspersed on your quest. Obviously this wasn’t exactly like Metroid due to that game being set in an alien world, but the method of exploration and traversal was quite similar.

Your immediate instinct at the beginning of the game was to go right, until you reach a boss room and then head on to the next stage. Well, that wasn’t exactly the case.

You quickly found yourself back-tracking out of no where ( just like the first time you played the original Metroid where you would just go right out of instinct only to find that you actually needed to head left first to get the morph ball). Yeah, back-tracking in a Castlevania game. This was, of course, unheard of back then due to the original being a linear, side-scrolling experience.

It came as a shock to most but after messing around in the game world– talking to townspeople, running through mansions, receiving cryptic clues, hunting down Draucla’s remains, fighting or running from the bosses, and being met with “what a horrible night to have a curse” at the most inconvenient times– one found that this was truly a Castlevania game. It was just in a different style which would then go on to sprout one of the greatest games of all time and a pair of handheld trios in the same template.

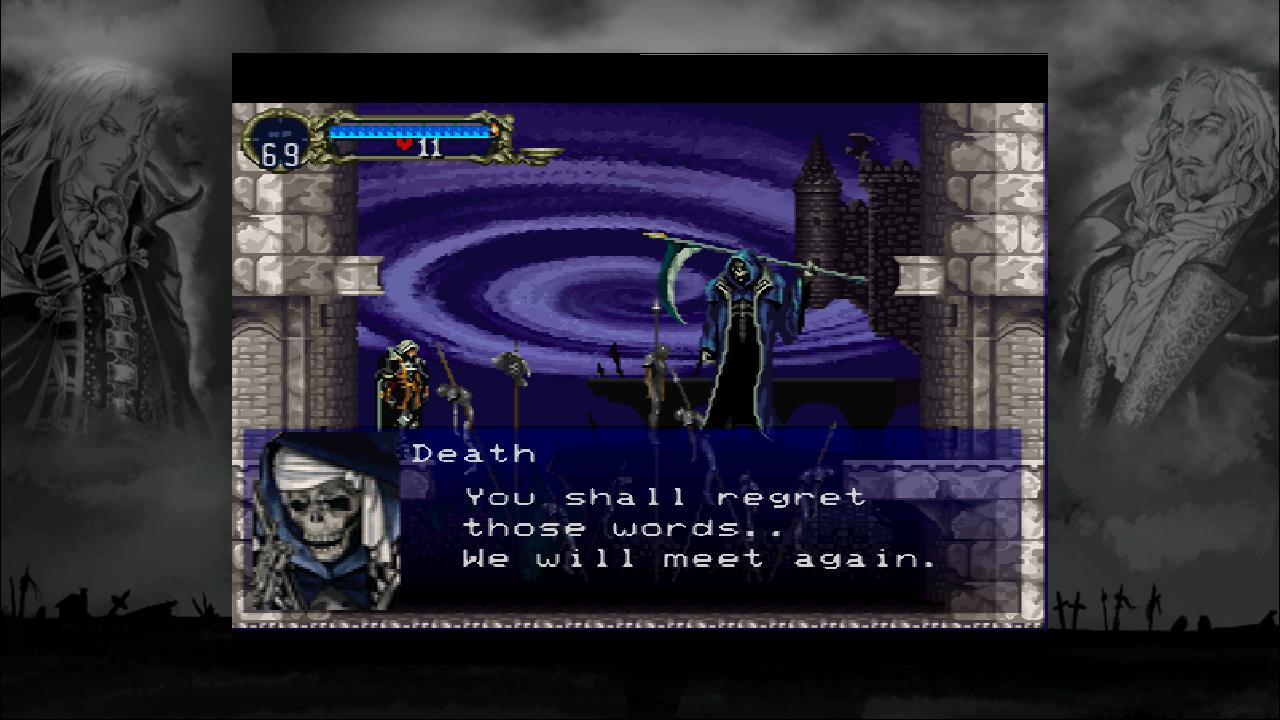

Then comes Symphony of the Night. What else can be said about this gem that hasn’t been said already? The game is heralded by many as one of the finest games of all time and also seen as one of the best ‘vanias. What’s also significant about this game is its strong ties to Metroid, from a gameplay perspective. So much so that it paved the way for 6 other games developed using the same formula; a genre that came to be known as Metroidvania.

Whereas Simon’s Quest was akin to Metroid due to its back-tracking and having to figure out where to go next, Symphony of the Night was even more like Metroid due to its style of progression through the castle(s). It wasn’t just about knowing where to go anymore, though that was still prominently the case, now it was also about finding the corresponding ability and/or item to proceed through the game.

After the game’s epic intro, complete with “epic” voice-work, you’re put in the role of Alucard and not much time passes before you’re stipped of all your valuables by Death. From here on, with nothing but your fists at first, you have to stock up on weapons, pieces of equipment and other items necessary for your survival. But that wasn’t it, you also had to seek out actual abilities like the Bat, Wolf and Mist transformations. These were actually vital to accessing areas in the game.

Exploring the whole castle in Symphony of the Night was no small feat, the iconic edifice was huge on its own but then you add the existence of a second castle (which was a reverse version of the first one with new monsters to fight and, once again, Dracula’s remains to collect) and you know you’re in for one lengthy but truly satisfying adventure on your way to cease Dracula and his antics. But that’s after you actually figure out how to get from place to place, though.

Like Metroid, Symphony of the Night pit you in a sprawling world instead of singular stages, like the classic ‘vania titles and other old-school side-scrollers. See a gate-like door blocking you from going any further? Just come back once you obtain the Form of Mist. See a long opening above you that’s in no way accessible without any sort of aerial ability? Come back when you have Form of Bat. Want to know how to get the best ending? Come back when you…No, wait, I’m not telling you!

But it’s not hard to see how much Symphony of the Night borrowed from Metroid or most notably Super Metroid with its design and style of non-linear progression. An influence which then applied itself to the three GBA and DS ‘vanias.

So, after creating one of the finest games of all time, where does Konami go next with the Castlevania series? Well, logically, a well-grounded business move would be to replicate the success of whatever worked and go from there. Despite not having outstanding sales initially, Symphony of the Night was still seen as the benchmark and template for what a Castlevania game could be. So, for the years following the success of Alucard’s second outing we got jus that: six 2D ‘vanias within the same mold of SotN.

The first three of those six Metroidvania-styled entries landed on the Game Boy Advance while the remaining three hit the Nintendo DS. This, of course, leads us to believe that we’ll be getting another trio on the 3DS, but that’s a story for a future column! So, what “new” did these handheld entries bring to the table? I mean, they couldn’t just be carbon copies of what made Symphony of the Night work, right? Right?

Well, yeah. Circle of the Moon had a robust DSS feature which let the player collect and combine cards to see their effects through Nathan’s attacks and stats. Harmony of Dissonance had some magic thrown into the mix as well as collection having to do with Dracula’s remains, akin to Simon’s Quest. Aria of Sorrow, and its direct sequel, Dawn of Sorrow, boasted a very addictive soul system which gave the game(s) a “gotta catch em’ all” feel. Then you had Portrait of Ruin and of Order of Ecclesia, the latter of which brought back the classic series’ sense of difficulty and somewhat linear stages to plow through, the former served as a superb 20th anniversary game which gave a nice modern spin to the original game, even including the iconic bosses from said game while also providing a very neat co-op system.

But one thing all of these games had in common was the notion of needing certain abilities to access further areas in the game. They were all within the Metroidvania genre and thus ,weren’t linear affairs. They even offered players multiple endings, each depending on different credentials one would have to fulfill. Order of Ecclesia, though, did a good job of giving fans a more traditional approach and thus the best of both worlds by offering huge environments in which you have more control over exploration along with smaller locales interspersed throughout which definitely brought back memories from the classic titles in which you didn’t have to worry about getting lost; you just had to make sure you get your ass to the boss waiting at the end of the stage. Hell, they even had a village like Simon’s Quest, complete with NPCs to interact with.

There’s no denying the impact Metroid had on the Castlevania series, especially post-Symphony of the Night. The strong influence led the vampire-slaying series into a different style of gameplay. You still did battle with creatures of the night and other demonic monstrosities, but you now had a different way of traversing through the game’s world. Huge castles were prominent in the Metroidvania entries, making some fans yearn for the series’ more linear days in which the whole experience wasn’t confined to Dracula’s castle.

But still, Symphony of the Night and the games that came after it, using the same template, all serve very important roles: Not only are they all outstanding games (yeah, even HoD in my opinion) but they all served to bring in fresh new faces to the series while also catering to the series’ loyalists who’ve been there since Simon Belmont first cracked his whip in front of Castlevania’s front gate all those years ago.

So, in celebration of Metroid’s 25th anniversary, we say thank you to Nintendo for giving us one of gaming’s most iconic franchises. And also, we say thank you, as ‘vania fans, for paving the way for one of the best Castlevania games of all time, and ultimately, one of the best games of all time, period.

JBoc924

JBoc924