There is an existing phenomenon across every culture that the traditions and folklore of any other culture besides their own is more appealing. People hold superstitions and retell the folklore of their own culture without the reverence and attention they pay to those of a different people. This is especially true in horror, where fans happily join long, spirited discussions about themes foreign to their own experiences. In this series, I’d like to explore the cultural influences that birthed popular horror themes and tackle the origins of monsters whose grasp has now extended beyond their home.

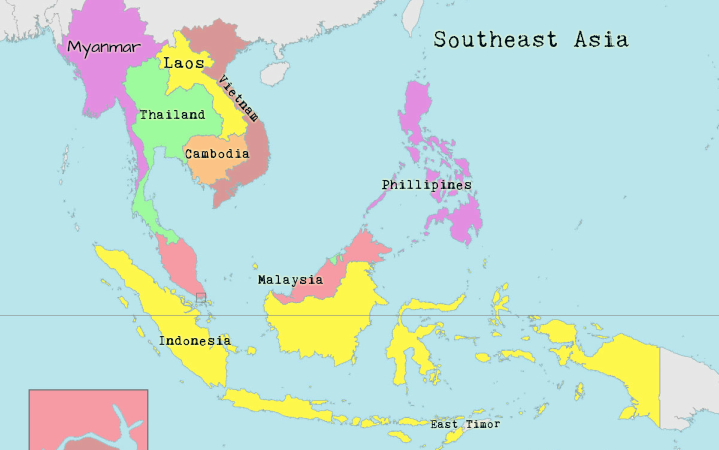

We are beginning with the traditional folklore of Southeast Asia, which inspired the creation of this series. We will delve into the main themes of superstition, folklore, and mythology in the area, with a focus on Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, and Cambodia. We will be directly referencing the enemies found in the DreadOut series and Nightfall: Escape. If you haven’t played those games yet and don’t want to spoil the surprise, stop reading here and save this article for later.

Southeast Asia has more monsters and supernatural beings than we could ever hope to catalogue in a single game series, and enough to fill a dozen titles. Across the entire region, I came across more than one hundred separate entities. I also noted an overlap in certain folklore that were almost identical across borders, and were present in multiple countries under different names. These apparitions are among the most dangerous, according to the stories, and are the ones found most commonly in exported horror.

It is likely that the larger geographical distribution of these stories makes them a better bet for an entertainment producer, increasing the chance that surrounding populations will purchase their game or movie. It is also likely that these stories are among the most common in media because they are the most grotesque of the local lore. These creatures can be sorted into three main categories: Pregnancy, Greed, and Tradition.

Pregnancy

The most common thought I had about the ghosts in DreadOut was that there were a lot of beliefs that directly involved pregnant women and babies. Researching for this article, I found that the game had only scratched the surface of beliefs about pregnancy and childbirth. These monsters go by different names from country to country, but most span the entire region and are among the most common beliefs to actually affect the way people behave.

The stories have some elements in common that help dredge up their origin from their murky pasts. The spirits are commonly blamed for illnesses that affect women in rural areas, as well as maternal death and stillbirth. The maternal and infant death rates, as well as stillbirth rates and child death rates, are particularly high in Southeast Asia. While strides have been made in cities, lack of access to skilled medical professionals and a structured healthcare system left rural women without many of the improvements seen by their urban counterparts. The gap in medical access for rural women has closed significantly in the last five years, though women in Laos, Myanmar, Cambodia, and Indonesia still see higher infant and maternal mortality rates than the global average. These historically high rates of tragic outcomes likely led to the belief that many of the ghosts thought to roam the region were attacking pregnant women and babies, giving some relief to families grieving in the aftermath. The beliefs also allowed pregnant women to feel empowered in controlling the risk to their pregnancy in the absence of medical help.

The countries of Southeast Asia have a dual concept of healthcare, encompassing both traditional healing and modern medicine. This meshing of traditional and modern medical interventions has led to several studies on the ways these beliefs impact healthcare outcomes and planning. The National Library of Medicine has an available abstract that looks into the reasons healthcare practitioners have to take the beliefs seriously and incorporate them into treatment plans. The study it is connected to warns that patient compliance is directly related to their need to balance both approaches, which presents a legitimate need for physicians and nurses to respect their spirituality in health planning.

Southeast Asian beliefs about pregnancy, childbirth, and the 30 days following birth are closely tied to their religious beliefs, as well. During the 12th century, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism came to Southeast Asia with importers as global trade developed. Buddhism outpaced the other religions in uptake, meshing well with the existing beliefs of locals. Islam became the predominant religion in certain areas which had a high Muslim immigrant population. Both religions contain strong beliefs regarding conception, a woman’s duties during pregnancy, and the act of childbirth.

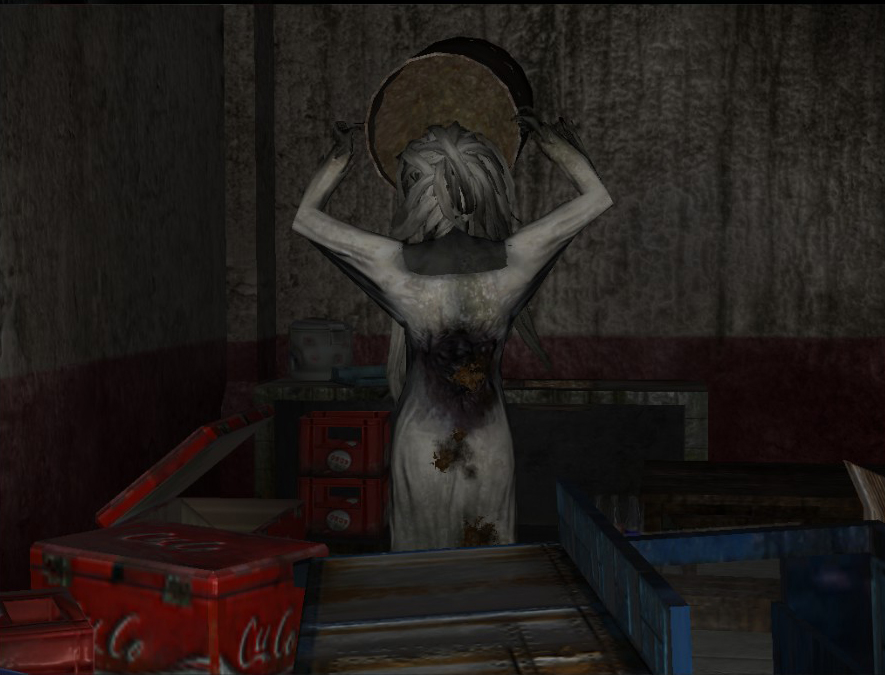

Buddhism, especially, contains beliefs which align closely with the folklore of the region related to pregnancy and the ghosts that target pregnant women. The most common ghost of this type in Southeast Asian folklore is the a beautiful young woman who appears as a floating head with her entrails still attached. She is said to be a woman who practices dark magic, and must take this form as punishment. She wanders rural streets at night, feasting on feces, chickens, and blood to feed her voracious appetite. She has a long proboscis tongue that allows her to feed on the placenta of an unborn child, which is believed to spread disease to the infant and cause stillbirth. Pregnant women are advised not to go out alone in the evening, and to ignore frightening sounds coming from outside of their home at night so that she cannot attack. She appears in DreadOut as the Palasik, the most common name given to this monster in Malaysia and Indonesia. She is known as the Ahp in Cambodia, and the Krasue or Kasu in Thailand and Cambodia. While there are slight variations in the origin stories for each country, her appearance and behaviors remain the same.

The most common archetype of pregnancy-related ghosts in the region is the woman who died in childbirth, or lost her child. Thailand’s Mae Nak is my favorite version of this ghost, telling the story of a woman who died along with her baby during birth while her husband was at war. When he returned, he found both alive and well, and lived happily with them for a while. Eventually, he learned from the townspeople of their true fate and fled to a temple where she could not enter. Angry at the people for causing her husband to leave, Mae Nak terrorized and killed them until she was captured by a local priest. Some legends say she was convinced that passing on to reincarnation would reunite her with her love, while others say a shaman stored her soul in a bracelet made of her bones and used her to do his bidding.

This legend is incredibly similar to that of the Lang Suir and Pontianak, present in the cultures of both Malaysia and Indonesia. These are the hostile ghosts of the mother or child who has passed. These spirits attack mothers and infants out of jealousy for the lives they were unable to enjoy. Both share similarities to the global idea of the vampire, feeding off of the blood of their victims to gain strength. The legend allows that women may protect themselves and their child by keeping a pair of shears or a blade nearby, which the ghosts will avoid out of fear. Similar legends involve the ubiquitous “white lady”, called the sundel bolong in Indonesia. This is the ghost of a prostitute who died while pregnant. She appears as a beautiful woman in a white dress, and she uses her long hair to hide the hole in her back where her child crawled out of her body after her death. These stories often say that you can tell when these spirits are nearby by the sound of their laughter, allowing women to avoid them.

Greed

The second most common theme in the spirits of Southeast Asia is greed. Jealousy, trickery, and a desperate desire for youth combine into ghosts which seem more annoying than dangerous. There are many names and presentations for ghosts who answer to people practicing black magic, used as minions to help their master. These spirits are usually sent on missions of theft, or to create trouble for a rival, though they can cause death or injury in some cases.

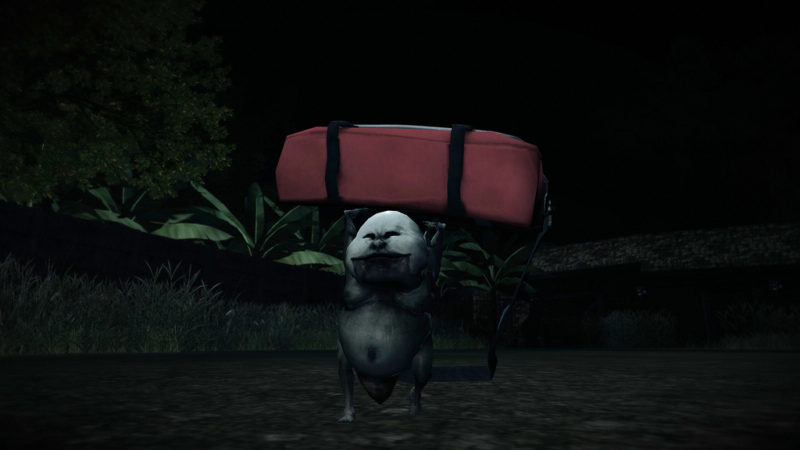

The jenglot is a living creature that looks like a small doll made of human hair and skin common in Malaysian and Indonesian culture. The jenglot must be fed regularly to keep it happy and in service, and it prefers to be fed blood. There are actually people in some areas of Southeast Asia currently keeping dolls they believe to be living jenglots in their homes. They purchase blood from a butcher or, less commonly, the Red Cross to feed their jenglot and keep it from wreaking havoc in their own village.

Similarly, the toyol are servants to a master’s bidding. These are the reanimated remains of stillbirths controlled by wicked men. They are used to steal small objects from neighbors, leading to a common tradition of keeping money and small valuables in front of a mirror. They can also be stored with needles around them, as toyol will avoid mirrors and needles, and thus your valued possessions. Toyol can be distracted by scattering marbles or small toys around the floor of the home, or by leaving a pot of beans out for them to count. They are fickle, and will turn on their master if he neglects to leave eggs and milk out for them daily. Toyol appear in the mythologies of Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore, and Brunei.

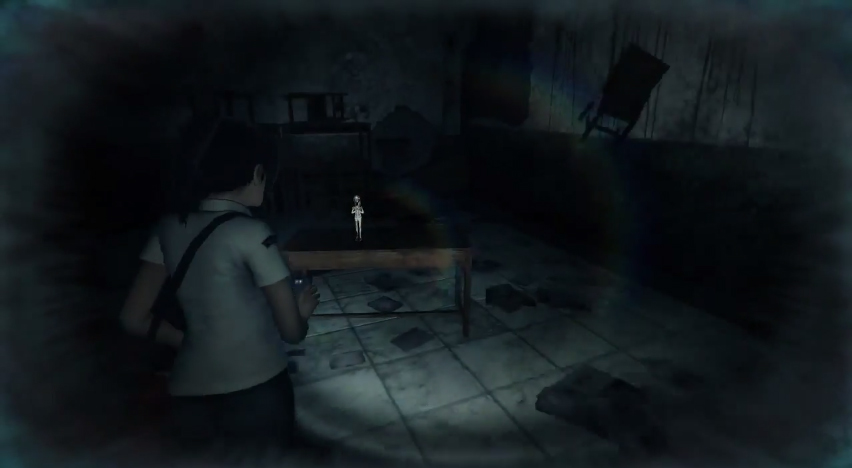

The toyol’s less-disturbing counterpart in Thailand is the luk thep, a doll believed to house the soul of a dead child and bring luck to its owner. Luk Thep have become so commonplace in Thailand that mental health officials are having to convene to address when to intervene as mental health professionals. Airlines in Thailand are accommodating the dolls as though they were living children, serving them snacks and drinks. Buddhist monks are performing ritual blessings on the dolls, and shops have popped up in metropolitan areas to sell clothes and accessories for the dolls to increase the fortune they may bring. While toyol are the grotesque domain of evil men, luk thep are considered benevolent and do not suggest wrongdoing by their caretaker.

Women are not left out of the consideration of greed and misleading others for personal gain. The practice of using sususk, or charm needles, dates back centuries in the region. Thin needles of diamond, steel, or gold are placed under the skin by a spiritual practitioner, and are believed to make a woman more beautiful, stop her from aging, or make her more charming. They can also be used to influence finances and popularity, but must be removed before death. When a woman with sususk is old and becoming frail, the same practitioner must remove the needles, or the woman risks a difficult death or inability to pass on and be reincarnated. The use of charm needles is still alive, uncovered most commonly by modern dentists when patients are given facial x-rays for oral care. While the use of charm needles is most common in the cultures of Malaysia and Indonesia, it has been found recently as far as mainland China and India, and appears from time to time in Cambodia, Thailand, and Laos.

Other apparitions in the region are a result of greed or dark magic during a person’s lifetime. Indonesia’s babi ngepat is a spirit that appears as a large boar. This form is the punishment for the souls of those practicing black magic for financial gain, forcing them to guard their treasures instead of being reincarnated to the next life. Many other names and ghosts refer to people suspected of practicing black magic for wealth or immortality, as well as those suspected of misleading others for personal gain. A widespread belief in the use of dark magic is the basis for region-wide belief in the possession of living bodies by evil spirits, often used as a way to explain sudden poor health and the symptoms of mental illness or a change in behavior.

Tradition

The third major grouping of ghosts in Southeast Asia are those whose appearance is based in a failure to follow the customs and traditions of the region. There are many traditional rules regarding funerals, wakes, and burials. Pregnant women, of course, are not to attend funerals or go to grave sites, as they will likely attract the attention of angry ghosts. Beyond that stipulation, there are traditions in the handling of the dead that result in unwanted ghostly activity if ignored. Southeast Asia is home to a host of folklore and tradition regarding the burials, and Indonesia’s Toraja people are lauded for the most complex burial traditions in the world.

The most common of these graveyard ghosts is the pocong of Malaysia and Indonesia, a spirit who hops around looking for someone to cut the traditional burial shroud from its corpse. The burial shroud is meant to be untied before the burial takes place, but when left, will result in the spirit hopping out of its grave, unable to pass on. Pocong are not necessarily evil, but can become agitated, mischievous, or fall under the control of those practicing dark magic. Pocongs can be prevented by following the correct burial procedures and ensuring that the burial shroud is untied, so that the deceased may walk peacefully into the next life. Ghosts similar to the pocong can be found in the countries of Southeast Asia practicing Islam, which provides the basis for the belief that the soul has become stuck.

Another common character meant to support social traditions is the “Hungry Ghost”. Generosity is an extremely important concept across all of Asia, as it is both one of the main contributors to karma in Buddhism and one of the five pillars of Islam. Hungry ghosts are ghosts born of a lack of generosity in life, often considered to be the result of not sharing food with the hungry. Because of their failures, they are kept on earth as ravenous spirits who may only eat food left out for them by the living. This is one reason for the food offerings left out in many Asian cultures. The sundel bolong in the school in DreadOut can be seen in one room gobbling down an entire pot of food, which simply runs through her body before she disappears in search of more to eat. While no one deserves the fate of the sundel bolong, this one in particular can be assumed to have been less than gracious in her lifetime, given her incessant hunger.

The Filipino Aswang are part of the global mythology of were-beasts, but they have a special importance in the tradition of the wake. Aswang feed on humans, and will create an effigy of the person it kills out of banana tree trunks. The effigy returns home “ill”, and dies over the next three to four days. The aswang will also visit the wake of a recently deceased person and exchange their body for a banana trunk effigy if the body is left alone. Thus, it is important that the body always have someone at its side, lest the aswang take them and prevent the person from passing over peacefully. Aswang bear more than a little resemblance to Indonesia’s manananggal, which will observe the same opportunities to cause mischief if given the chance.

Other ghosts common to multiple countries deal directly with children who run off unsupervised, or who are mistreated, or young women who travel without the supervision of a protective male. Legends include an old woman who will hide children until their parents learn to care for them, and another who takes lost children and keeps them forever. Both stories seem to have the same origin, and reinforce the societal belief that children were the top priority. The Javanese people of Indonesia recognize Wewe Gombel, the “disheveled grandmother” ghost who frightens children who wander alone at night.

The even less friendly jinn known as genderuwo attacks and rapes women who wander the streets of Indonesia at night, and almost all of the female ghosts will attack men traveling alone after dark. The underlying theme that one’s place once night falls is in their home, with their family, is enforced through mythological creatures who will ensure punishment for those who are not. A few other ghost stories in the region deal with the spirits of women accused of killing others out of jealousy over lovers or beauty, reinforcing a social stigma against envy. More specific legends in each country deal with religious authorities who practiced dark magic, an especially egregious offence given their powerful position.

Final Thoughts

The folklore of Southeast Asian countries varies widely, but maintains some common ghosts under different names. Though their stories may fluctuate somewhat, the core of each remains the same. These ghosts have a strong basis in the largest religions of the area, Buddhism and Islam, and follow the core tenets of their beliefs about generosity, greed, family, and death. The stories also maintain a strong relevance to the death rates historically associated with the countries prior to industrial development and subsequent gains in medical care. The myths of the area enforce the ideals most important to the common religions, while also providing a way for families to resolve the grief of the loss of an infant or wife during childbirth. These ghosts, while frightening, can be traced directly back to the social beliefs of the region, and developed alongside these religions as they spread.

The ghosts who would choose to harm the living are outnumbered in all of the local cultures by ghosts who bestow fortune, guard homes and possessions, or help the lost and needy. While we did not focus on those benevolent spirits, they further support the notion that the mythology of the area is strongly based on the ideals of the main religions. The kind spirits help only those who are deserving, and the evil spirits focus on those who have strayed from the social norms of the area, or those in a vulnerable state who are more likely to suffer a poor fate.

The geography of the area does not seem to impact the traditions much, outside of its effects on the spread of trade in the 12th century, and thus the spread of religion. Some of the creatures are only found in the woods, but those are more concerned with why someone is so far from home after dark. None of the ghosts seem particularly tied to a given area, and all are considered capable of movement from one location to another. It would seem that the driving factors behind all of the malevolent ghosts of Southeast Asia are societal enforcement and explanation for tragic events.

Further Reading

The Myths, Folklore, and Legends of Southeast Asia

As Cultures Come Together, It’s All In Bad Spirits

Intersection of Asian Supernatural Beings in Asian Folk Literature: A Pan-Asian Identity

DestinyLeah

DestinyLeah