We here at Rely on Horror love horror games and game design in general. To celebrate both of these things, we will be publishing a new series of editorials here, titled Lest We Forget. Each month will bring two new examinations of narrative and game design in horror games. So how does one start such a monumental task? By examining something that pretty much every horror game has: flashlights.

The humble flashlight might be the most misused gameplay element in the genre. From first-person shooters to 2D side-scrollers, horror games have misunderstood the flashlight for decades. A good flashlight shouldn’t just add to a horror game’s immersion and sense of tension; it should also make sense in the constraints of the world and how it works. More often than not, however, flashlights are used in tandem with overwhelming darkness as a core gameplay mechanic. I’ll get to why that’s bad in a second, but first, let’s dig into how flashlights can aid the narrative.

For me, the ultimate flashlight in horror gaming is Silent Hill 2. Not so much because it works well as a tool to illuminate rooms, but because of how it’s introduced to the player. An hour or so into the game, James Sunderland comes across a modest apartment with a single mannequin standing in the middle of the room. A bright beam of light blazes from its chest; this acts as a gameplay marker indicating to the player to interact with it to add the flashlight to their inventory.

The position of the flashlight (and the foreshadowing this moment delivers) is but one example of striking and unnatural imagery in a series full of similar occurrences. Despite Silent Hill 2’s combat and puzzle design aging poorly, the opening hour’s approach to introducing players to its gameplay is still commendable in its structure. It presents an intriguing premise and supplies a series of small mysteries to investigate. Follow this trail of blood and learn about monsters and combat. Explore and find a flashlight to discover how environmental puzzles are layered.

Within the greater context of Silent Hill, it also makes sense — mostly — because it makes no sense. The town is meant to be a world gone mad, and this is one of James’ first big steps into his personal nightmare. While the imagery is artful and unnerving, it is surreal and out of place to find this clothed, flashlight-adorned mannequin in an otherwise vacuous room. With some beautiful, dramatic irony, however, it is also deeply integrated into the story; the mannequin wears the clothes of James’ deceased wife, and the flashlight later breaks when he discovers her true fate. These small details add value to a gameplay mechanic and thus add depth in a way only video games can: by tying gameplay to story.

Do all games need to tie their story to flashlights using small details intricately? Absolutely not. But more games need to acknowledge such an important gameplay device outside of a button prompt in a dark area. The opening moments of Condemned: Criminal Origins take a different, but no less effective approach to teaching players. After a police officer breaks his flashlight, you’re given a brief dialogue exchange where he tells you to use his while you’re both approaching a crime scene. It’s standard tutorial fodder, but in a greater context, it justifies why the player has a flashlight, while also granting them the agency to use it.

Gameplay devices like flashlights are meant to add variety and depth to navigating a game’s environment. Well designed games like Silent Hill 2 and Condemned manage to hide this thin motivation behind worldbuilding. The flashlight in Silent Hill 2 plays into the game’s foreshadowing and themes of illuminating one’s own psyche. The flashlight in Condemned represents a transference of power to the player’s perspective, preparing them for the rest of the journey. There are reasons for these flashlights to be a part of the player’s toolset, and they reach beyond an obligation to a genre trope.

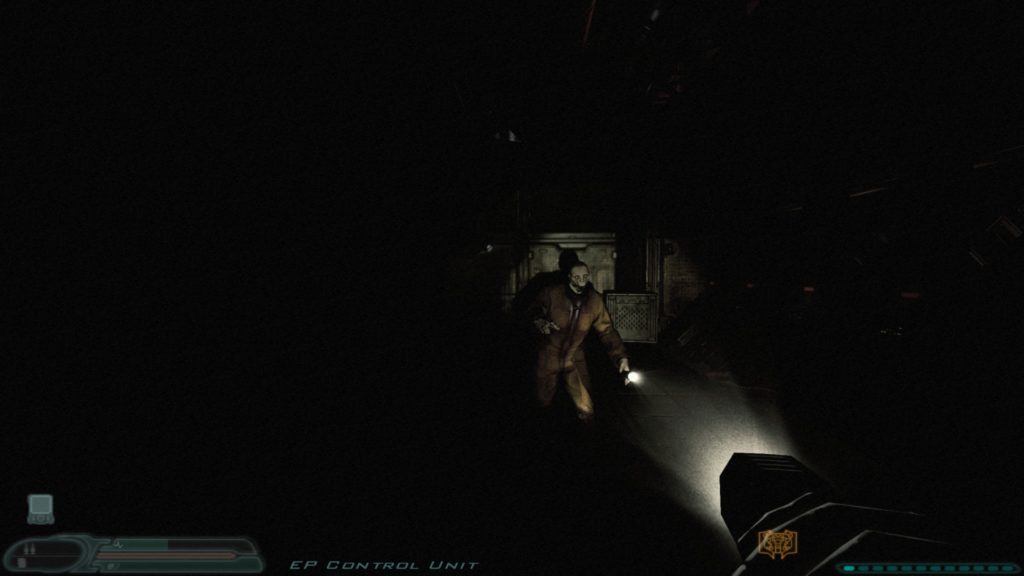

Too often do games simply insert a flashlight for no reason other than adding a semblance of depth to thin gameplay, teaching the player to use it as a crutch instead of a proper tool. This goes hand in hand with how many developers use darkness in games as a whole; instead of a mechanism to add atmosphere, it is another obstacle in the player’s path. To call this design lazy would be doing a disservice to the creative people who made these games. Instead, its a design choice that cuts to the heart of a common misconception about horror: that darkness itself is scary. In truth, the player should be more afraid of what the darkness hides. The perfect embodiment of this problem can be found in Doom 3.

Barring any mods or the BFG Edition that added flashlight functionality while shooting, the flashlight in Doom 3 is dreadful from top to bottom. In this super futuristic space base, there’s no reason given as to why Captain Generic carries around an enormous autonomous flashlight, aside from pure gameplay conceit. The execution isn’t great because the game doesn’t just obscure small details unless the player uses the flashlight, it obscures the whole game. Unless you raise the brightness to an insane degree, you cannot play Doom 3 without repeatedly switching back and forth between the flashlight and a weapon. It’s a burden forced on the player, and there is no contextual reason given as to why the player has one with such limitations. The game’s liberal use of darkness as a stand-in for tension and atmosphere is a problem unto itself, but a poorly implemented flashlight greatly exacerbates the problem.

Doom 3′s flashlight is an annoying blight on an otherwise solid game. The lasting issue is that while it released in 2005, horror games are still using terrible flashlights just like the one in Doom 3 to this day. Games like Daylight and Slender have insignificant narrative reasoning for their light sources — their implementation commits the same sins as Doom 3. Where they should organically fit into teaching gameplay moments, the player learns to rely on them as a crutch, hobbling through the overwhelming darkness. Making a game dark doesn’t automatically make it scary, guys.

Every element of game design is an opportunity to bring the player deeper into the world of the game. Does every game need a narrative justification for having a flashlight? No. Does forcing the player to treat a flashlight purely as a crutch rather than a tool mean the game is automatically not good? Not necessarily. But it can be one of a thousand small missed opportunities that can contribute to an overall forgettable experience.

What makes games as a whole fascinating isn’t what the player is doing, but why they are doing it. Giving purpose to the smallest details — even a flashlight — can be key to crafting an experience that stays with players long after they put down the controller.