For myself and many others, the original Dead Rising was one of the defining games of the Xbox 360/ PS3 console generation. A console exclusive that showed off the raw power of Microsoft’s new console when it launched in 2006, Dead Rising is the rare title that is as unique today as it was when it came out thanks to its level design, combat, and intimidating difficulty. Even after sequels, spinoffs, and a variety of games that took influence from its zombie-RPG premise, there’s still nothing quite like the first time.

My first experience with Dead Rising was in middle school. While I had played a decent assortment of horror games and shooters, I had never played a game that was so freeform and allowed for so much improvisation. The ability to go anywhere in the mall, use anything as a weapon and eat or drink whatever I wanted was a revelation to me. With progression that carried over between runs and unique survivors to find and save (if you choose), Dead Rising was an intricate game that invited replayability, and I obliged, dumping hundreds of hours into Frank West’s claustrophobic undead adventure.

Dead Rising is a game I have a deep, unyielding love of, but I’m not blind to its many flaws. Players are purposefully underpowered during their first run, and strict time limits for story missions can easily lead to failure and need to start the story again from the beginning. Combat is also animation-heavy, and fighting against other humans can be a frustrating cycle of getting knocked down before being able to retaliate.

But almost like another game series with roots in animation-heavy beat-em-up combat, Yakuza, Dead Rising‘s numerous faults don’t detract from the overall experience. The game is designed with many of them in mind, taking what could be needless frustrations and turning them into eccentricities. The result is a game that isn’t for everyone; the original Dead Rising has its fair share of rough edges, but the experience is meant to be learned over time.

Like modern games in the Dark Souls mold, the growth of the players experience in Dead Rising matters just as much, if not more, than the game’s own light-RPG system. Learning enemy patterns and weaknesses, and committing the mall’s layout to memory can completely change how a player approaches the game. For example, did you know that a katana is available in the game’s first area? It’s off the beaten path, but one of the game’s strongest weapons can be easily found if the player takes some time to explore Dead Rising‘s richly detailed environment. It also respawns upon re-entering the area, meaning that once the player has that knowledge, they are free to utilize it at any point.

All of this is to say that Dead Rising, while flawed, is still a great game because it’s interesting. It doesn’t try to be palatable to everyone’s tastes, and it doesn’t need to be; good art shouldn’t. Over time, the Dead Rising series would innovate with improvised weaponry and bigger areas to explore, but much of the series’ core remained; time limits, animation-heavy gameplay, and memorable, detailed environments. That is until the series soft reboot Dead Rising 4.

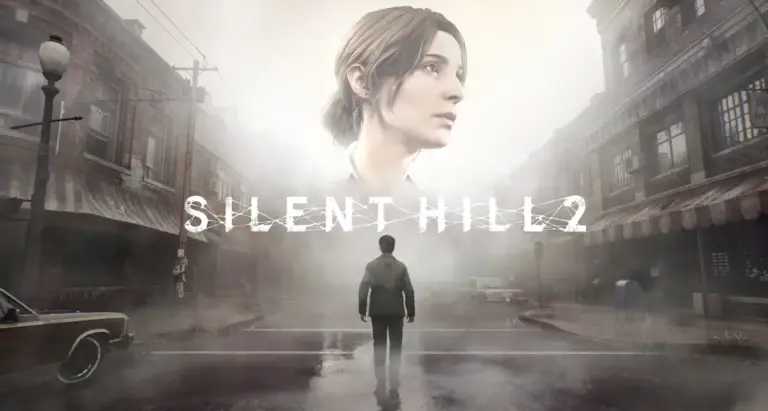

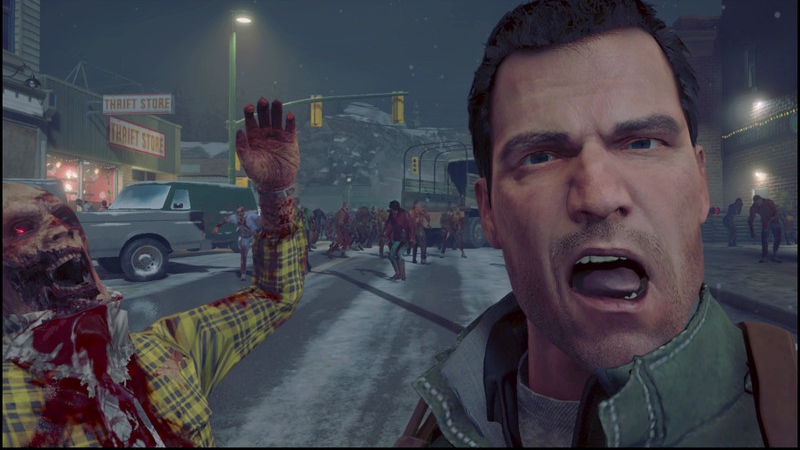

Out of the gate, Dead Rising 4 seemed like a great chance for the series to return to its roots. Bringing Frank West back as the main character and set in the original game’s Willamette in the aftermath of a Black Friday zombie outbreak, it felt like an attempt to update the series to remain relevant in a new console era. Unfortunately, it was met with tepid sales and lackluster responses from critics and longtime fans alike. Unlike other Capcom IPs that have seen soft reboots in recent years like Resident Evil 7, Dead Rising 4 completely missed the mark on updating what made the original game’s formula so interesting.

Dead Rising 4 takes every rough edge of the franchise and tries to sand it down for the sake of mass appeal. In the process, it loses so much of the charm that made the original game and its sequels stand out in a crowded open world market. The animations for combat are snappier, but the differences between most weapons are gone. The world is much larger and there are tons of collectibles to seek out, but the environments themselves are less detailed, missing the need to memorize every nook and cranny.

Perhaps most contentious to fans was the lack of any time limits, taking a series predicated on players’ prioritizing objectives and turning it into a standard open world game. Survivors encountered through the world aren’t unique encounters and no longer need to be escorted to safety, eliminating a large part of player’s need to learn the environments and return to a safe house. Memorable psychopaths are also replaced with flashier enemies that don’t get introduction cutscenes and don’t require much strategy to defeat.

Dead Rising 4‘s marketing focused on over-the-top weaponry and a variety of silly ways players could dispatch zombies, and it’s clear a lot of attention was paid to these elements in development. While Dead Rising has always been a ridiculous series, Dead Rising 4 veered closer to Saints Row with zombies than a return to form for the series. Gone was the sincere strangeness of Dead Rising‘s psychopaths and Frank West’s awkward mannerisms. Remember the weird, unexplained cult that showed up halfway through Dead Rising? How weird it was that new enemies just popped up without impacting the main story? Dead Rising 4 doesn’t have anything like that. In sanding its edges and trying to maintain some semblance of humor, Frank West’s return devolves into meme humor shenanigans, hoping goofy outfits and big guns distract the player from noticing the game’s missing heart and soul.

In many ways, the game represents the worst of AAA game design. In Dead Rising 4, the game’s perceived depth doesn’t come from inviting players to learn the game’s secrets, environments, and mechanics. Instead, Dead Rising 4 takes the Ubisoft approach and gives players a huge world filled with lots of stuff to do and no particular reason to do it. The biggest additions to Dead Rising‘s formula are Batman-style investigation sequences, Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare-style Exo-Suits, and Mad Max-style vehicles.

These additions might make Dead Rising 4 more palatable to a wider audience at first glance, but the game never innovates meaningfully on these concepts. The result is a formless melange of AAA design tropes that will be familiar to anyone who’s played a video game in the last decade. That familiarity is Dead Rising 4‘s downfall; the game spends so much time chasing trends it quickly loses any identity of its own. On all technical levels, Dead Rising 4 is a decent game, but without the pieces of design that made the original titles memorable, it’s not an interesting one.

As I write about the disparate elements of Dead Rising 4, I can’t help but think about Resident Evil 6. Another Capcom title stuffed to the brim with stuff and vaguely molded in the shape of other popular titles like Gears of War and Uncharted, Resident Evil 6 infamously aimed for mass appeal and fell well short of the mark. Both Resident Evil 6 and Dead Rising 4 did their best to “westernize” their respective franchises for the AAA market, but fans didn’t fall in love with those games. The Dead Rising series earned its fans by being different, by sticking out from the crowd; by being an interesting game, even if that meant it wasn’t suitable to everyone’s tastes.

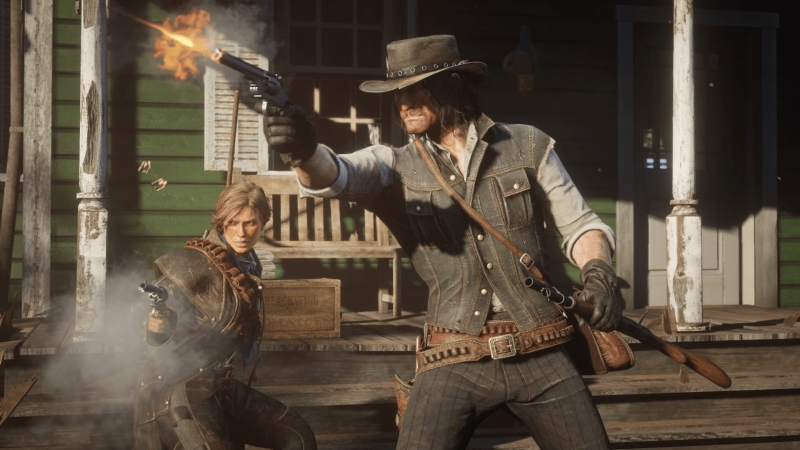

In discussing what constitutes a good game versus an interesting one, I can’t stop thinking about 2018’s Red Dead Redemption II. The successor to one of the most hailed open world games of all time, Red Dead Redemption II has drawn a copious amount of flack for introducing cumbersome new mechanics to Rockstar’s open world repertoire, including hunger and stamina meters and a finicky control scheme.

It’s the exact opposite of what happened from Dead Rising to Dead Rising 4. Where Capcom decided to remove any prohibitive barriers to enjoyment for players, Rockstar took a mostly straightforward gameplay formula and complicated it. As one of the biggest AAA games of the year, a lot of people were immediately turned off. They went into Red Dead Redemption II expecting a long, drawn out western, sure. But they didn’t expect the game to have a complicated control scheme or meter management.

I love Red Dead Redemption II much in the same way I love the original Dead Rising. Both are deeply flawed games, yet unlike anything else I’ve ever played. Mechanically, their systems inform their narrative well and manage to draw the player deeper into the world of the game organically, allowing for unique systemic moments that differentiate each player’s experience. They are interesting games, and they aren’t for everybody.

As I’ve read various thinkpieces about Red Dead Redemption II being needlessly cumbersome and overstuffed with meaningless busy work, I can’t help but shake my head. There are salient points to be made about RDR2‘s shortcomings, but these aren’t them. It’s a game that isn’t constantly badgering the player’s attention span with map icons and explosive setpieces. Red Dead Redemption II sets its own pace, and if the player isn’t down with it, they don’t have to play. There are a lot of problems with Red Dead Redemption II, but at the end of the day, it has an identity of its own. It’s an interesting game.

Examining Dead Rising 4′s flaws expose some of the deepest failings of the AAA game industry, but also in how the game industry approaches games as an artform. No film critic would say that their favorite films are objectively flawless, just like no art critic would say their favorite installation should be meaningful to everyone. In a space that spends as much money as AAA games, mass appeal is an understandable tactic, but it’s not sustainable to the consumers because everyone’s tastes are different. The Dark Souls series understands this. Capcom saw the error of their ways after Resident Evil 6 and made Resident Evil 7 a much smaller, but more interesting game.

The failure of Dead Rising 4 is a valuable lesson for developers, journalists, and AAA companies alike. Even with their flaws, players want games that are interesting, not just shiny and new.

Bad_Durandal

Bad_Durandal