When I finally got around to playing Outlast 2 late last year, I was pleasantly surprised to find that, not only was the game a finely crafted adventure that fixed many of my complaints with the original Outlast, but that it also packed a hefty narrative punch. The entwined stories of a journalist rescuing his wife from a doomsday cult interspersed with flashbacks of a childhood tragedy he witnessed at a parochial school struck a chord with me.

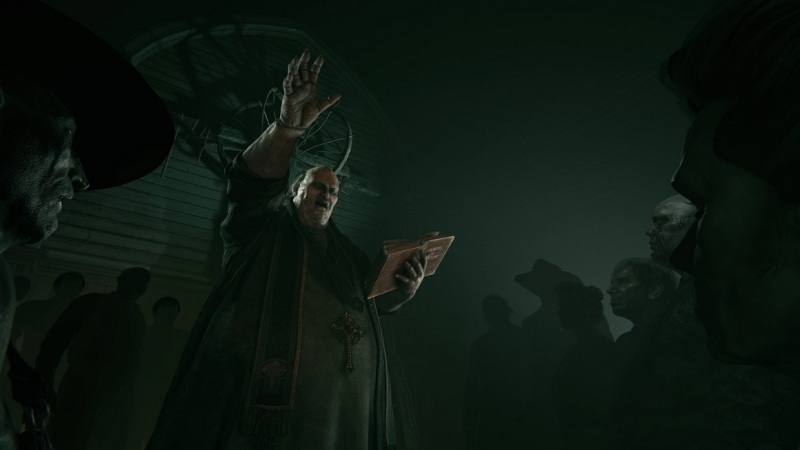

Outlast 2 is a bit of a mess with its themes, but that doesn’t deprive them of depth. Blake’s search for his wife leads him to uncover the religious cult of self-appointed prophet Sullivan Knoth, and the conflict between Knoth and a rebelling satanic cult led by a woman named Val. Knoth is given almost no depth as a character; a purulent caricature of religious hypocrisy, he uses his post to manipulate his followers into heeding his every want, including copulation. He bends the words of the peaceful Jesus Christ into fear-mongering messages of hate, preparing his “flock” for the apocalypse and keeping a watchful eye for the Antichrist who heralds its arrival.

In many ways, Knoth could be perceived as a thin parody of modern Conservative American Christianity. He turns a blind eye to his prejudices and sins, justifying them because — as the sole appointed — he alone is “truly forgiven.” Any mayhem or violence his sect causes to others is for the greater good, to protect the flock, and maintain his interests. There are coincidental alignments with self-forgiving conservative-leaning ‘Christians’ in America who somehow shrug off their support of people who bomb civilians or separate children from their mothers every Sunday. More than that, though, Sullivan Knoth represents modern Conservative Christianity’s views on sex. This is not strictly in the coital sense. Thanks to in-game documents we know that Knoth slovenly takes part in both consensual sex and rape of vulnerable female cult members, despite decrying the sexually immoral.

I’m specifically talking about sex in a broader sense here, particularly as it pertains to cisgendered women and their reproductive organs. When Knoth learns that the antichrist is to be born from his flock, he orders every baby murdered. Before this revelation, abortion was a sin in the cult; Knoth even encouraged sex as a way to grow the flock.

It wasn’t until it affected him that abortion stopped being a sin and became a necessity to survive. Both the wonton sexual depravity Knoth engages in and his ordering the death of children are stains upon his character. They resemble the “do as I say, not as I do” mindset that seems so commonplace in the hierarchies of modern Christianity (and, by extension, Catholocism), whether it be abortion scandals or church cover-ups for pedophilia. When someone else has sex and gets an abortion, they’re morally reprehensible. When you do it, the Lord forgives.

Here, the analogy could end. In constructing such a sleazy, cartoonish figurehead to lead Outlast 2‘s doomsday cult, the game directly invites comparisons to real-world conservative Christianity in America, thinly veiling its contempt for modern religious hypocrisy with all the subtlety of a nail to the groin. But merely examining Knoth’s place in this story is to ignore the larger picture Outlast 2 paints of how sex and gender are regarded in Christian America. To find a deeper meaning, we need to talk about Val.

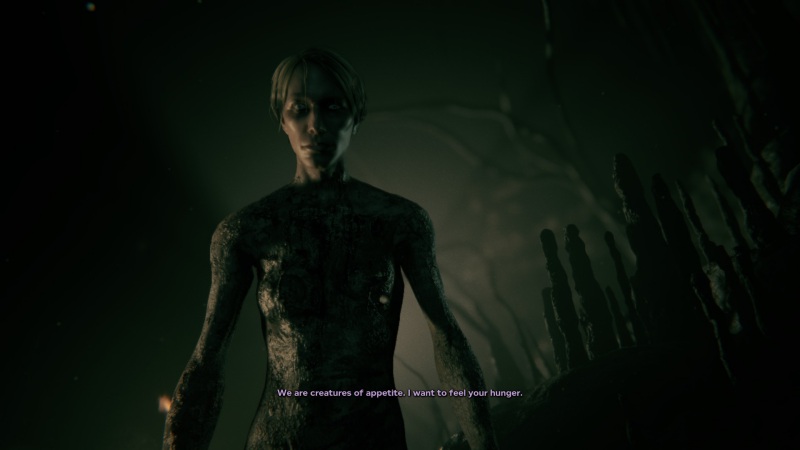

Val, as a character, is similarly lacking in any character depth. A spindly blonde transgender woman who delights in sexual promiscuity, she was once a dedicated servant of Knoth who defected, starting her own heretical cult with the intent of bringing about the antichrist. While she has promise as an interesting character, she is underutilized throughout Outlast 2‘s narrative.

Her thematic importance is utilitarian; if Knoth is conservative Christianity’s lust for power at the expense of hypocrisy, then Val is Liberal Atheism’s sacrilegious revolt. Like a rebellious teenager in a staunchly conservative household, she rails against Knoth’s sacraments in every way possible. She gleefully flaunts her sexual immorality and blasphemes Knoth and his teachings. During the game’s climax, she partakes in an orgy-like ceremony with Lynn to facilitate the delivery of the anti-christ. She’s a reflection of a parody; equally ridiculous in her cartoonish convictions as Knoth is in his.

It is no accident that Val is also a trans woman; in Knoth’s brand of Christianity, women are subservient to the will of those in power because of gospels bent to make it so. In Val’s heretical cult, women are the leaders. Uninhibited by the gospels of men, they do whatever they want with their bodies whenever they want to, unafraid of their natural inhibitions. Despite having small roles (which is a valid critique unto itself), Val and Lynn are the most critical characters in Outlast 2‘s story because of how well they illustrate Knoth’s — and by extension Conservative Christianity’s — wish to control and suppress women who don’t adhere to his every whim. Sex, nudity, and childbirth are permissible in Knoth’s Christianity, but only with his blessing.

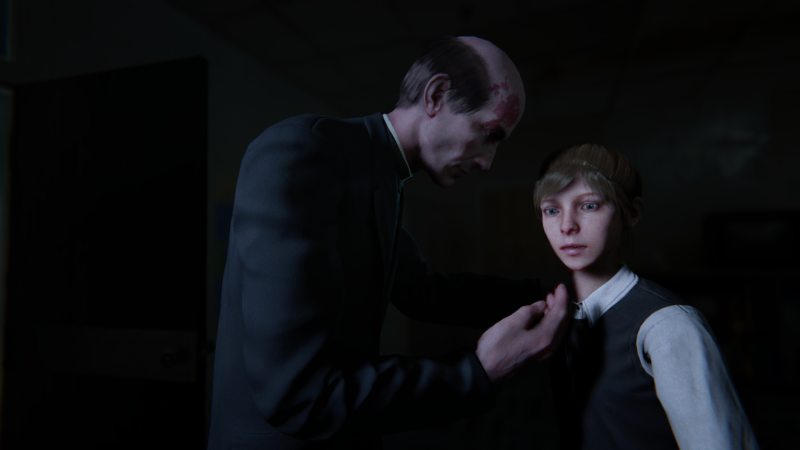

The final pieces to Outlast 2‘s sexually-frustrated puzzle are Blake’s flashbacks to his school days. Set in an ever-twisting parochial school, Blake’s quest to find Lynn is interspersed with being forced to relive the night where he witnessed Father Loutermilch abduct his childhood friend — and school crush — Jessica. From the very beginning, these sequences aren’t exactly subtle about how it will end. Nonetheless, they create a mounting sense of dread until the subplot is resolved.

One major point of contention for critics and fans of Outlast 2 has been the lack of cohesion between its alternating storylines. It’s true that they never come together, but from Blake’s point of view, the events of his childhood and Knoth’s cult are inexorably linked. Steeped in sex, abuse, and trauma, it’s only natural that living through the horrors of finding his wife would bring back repressed memories, aided by the mysterious sirens that trigger the flashbacks.

Blake’s perspective in Outlast 2 is important in not only what he represents, but how it manifests in between gameplay and narrative. From his eyes, we see Knoth, a slob who dominates the feeble-minded using religion. The other side of the same coin is Father Loutermilch.

Unlike vulgar hillbilly prophet Knoth, Loutermilch is a much more realistic and terrifying antagonist. He’s every parent’s worst nightmare; an eloquent, well-dressed wolf shepherding their precious lambs astray, hiding behind the word of God all the while. He doesn’t speak in feigned scripture or cackle maniacally as he reveals his evil master plan; in fact, he has very little dialogue at all.

His only real similarities to Knoth are sexual hypocrisy and a need to control others. When Blake tries to help Jessica, he’s instructed by Loutermilch to leave, threatening to call Blake’s parents if he disobeys. With Loutermilch leveraging his position of power over the children, Blake knows he doesn’t have a choice in the matter. Despite Jessica’s pleading, he leaves. Soon after, he hears her screaming and rushes to find her body hanging lifeless with Father Loutermilch standing nearby, telling him it wasn’t what it looked like.

Loutermilch is the perfect analogy for the darker, lesser-known kinds of control churches can exert over people. In the private hallways where he feels safest, his word is absolute, and dissent is met with violence for the sake of self-preservation. To the outside world, he’s a kind man — a trusted leader. He doesn’t rabble about who God wants him to fuck; he’s the kind of evil that shakes your hand on Sunday.

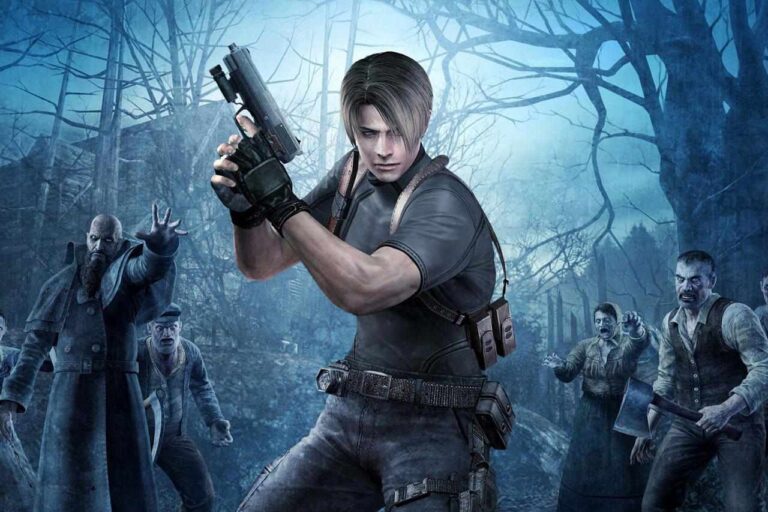

In the last installment of Lest We Forget, I drew parallels to themes of millennial disengagement with the ideal American family in Resident Evil 7. I did so to illustrate how well that game worked as an analogy for shifting familial values in modern America. In drawing similar parallels between Val, Knoth, and Blake in Outlast 2, the goal isn’t the same. The relationship between the cults, followers, heretics, and outsiders only works as an analogy in a vacuum; an American society where the only religious spectrum has fervent Conservative Christianity at one end and militant Liberal Atheism at the other.

Of course, this is ridiculous; not all Christians are radical. While American Christianity still heavily skews conservative, it’s not nearly the societal force it once was. In fact, there’s a sizable population of Americans that believe in God, despite not regularly attending services or adhering to any particular denomination. That’s not to mention the middle ground of liberal Christians, conservative Atheists, and everything in between.

Outlast 2 isn’t an analogy for American Christianity as a schism of conservative and liberal values. Instead, it’s an examination of one particular aspect of those values and how it affects believers and nonbelievers.

Outlast 2 is, at its core, a game about American Christianity’s fear of sex. Outlast 2‘s revulsion with lust and bodily sin isn’t a result of trying to scare the player; rather, it’s a symptom of how the game goes about critiquing the religious hierarchies it depicts. Val and her Heretics’ nude appearances are meant to appear strange and possibly horrifying to the player, sure. But their promiscuity is leveled as an insult directly to Knoth and his flock. It’s a radical method of rebellion against a system of control that suppresses the natural acts of sex and reproduction. Like Val and Knoth themselves, it’s not meant to be subtle. That doesn’t mean it can’t serve as a valid critique.

I recommend anyone interested in critiquing the themes of horror games to read Reid McCarter’s piece about Outlast 2‘s exploitative horror over on Paste. It’s a nuanced, well-presented argument that posits the game’s fixation with violent psychosexual imagery is at odds with its sturdy critique of religion in America. To each their own, but while he sees them as separate topics in Outlast 2‘s repertoire, I see them as inseparably conjoined.

The world of Outlast 2 is one of extremes; extreme control exerted over helpless people and extreme rebellion as a result. Like Voltaire criticized the Catholic church of the 1700s using absurd, comedic caricatures, Outlast 2 indulges in absurdity masquerading as straight-faced horror. It expertly wields its melange of disparate ingredients to depict why and when religions choose to control sexuality, and how often that choice is blatantly hypocritical. Outlast 2 is basically Candide with less ‘conveniently encountering old acquaintances’ and more ‘mutilated testicles.’

Bad_Durandal

Bad_Durandal