It is an undeniable truth that games — as pieces of art — always have something to say. For instance, even as far back as the original Resident Evil, the series has unfailingly featured some mount of subtext; it’s an integral part of any science fiction or horror narrative. Reading in between the poorly-voice-acted lines will quickly reveal the series’ very clumsy way of letting us know that power corrupts, and those in power don’t care about who they hurt. It’s an essential message that can be slotted time and time again into whichever dangerous biohazards Chris Redfield and Co. find themselves in. As the franchise reinvented itself into a lean modernization of its gameplay roots in Resident Evil 7, however, the series also found a new approach to storytelling.

The core story of Resident Evil 7 is simple: Players take control of Ethan Winters, a man whose wife Mia was kidnapped by the Baker family, a clan of redneck mutants and held hostage for the last three years. Upon finding her and her new “family,” he teams up with Zoe, daughter of the family patriarch. Ethan resolves to rescue his wife and put an end to the murderous Baker clan, who are revealed to be under the control of a child named Evelyn, a biological weapon. As I played through the story, I felt a deeper connection to the narrative beyond its plot points and devices. It occurred to me that Resident Evil 7 is more than a game about mutant cannibals and Texas Chainsaw Massacre references; the true existential horror of Resident Evil 7 is the desperation to escape from archaic tradition.

In Resident Evil 7, the game’s subtext relies entirely on the cast of characters, each of whom represents either a familiar or disruptive element of the traditional ‘Nuclear Family’ dynamic. For this analysis, I will be examining each member of the family one at a time, taking into account which political and familial archetypes they fall into along the way, and what they mean symbolically, starting with family patriarch Jack Baker.

From various notes and story bits found throughout the Baker house, we know that he is a military veteran who inherited the family ranch. The epitome of southern hospitality, he brings Mia and Evelyn into his home as soon as he discovers the crashed tanker in the Bayou, caring for their wounds and hoping to nurse them to health. In a late-game conversation with Ethan, he reveals that he isn’t a violent man, and wouldn’t willfully have hurt anyone if Evelyn hadn’t made him. He often speaks about the importance of family, even in his possessed form.

In all, Jack is a perfect example of the bygone stereotype of the bread-winning American father; a dutiful household leader who puts family above all else. He represents the traditional conservative, oblivious to the changing dynamics of the world outside his own. If Jack voted, it would likely be for a Republican. If he voted for Trump, it probably would have been in support of his promises to bring jobs to American workers, rather than outright xenophobia.

Together, Jack and his wife Marguerite make up the core of Resident Evil 7‘s traditional family values. Like a twisted 1950’s housewife, Marguerite spends her days cooking for her (cannibal) family and tending to her (mutated) greenhouse. She has several voice lines condemning Ethan and Mia’s sexual relationship; a relic of outdated attitudes towards sex in America. Like Jack, she wants nothing more than to keep her “family” together, even trying to turn kidnapped people by feeding them infected human remains. A loving mother to match a caring father, they sired two children whom Marguerite raised while Jack worked on the ranch. They live an archaic idea of the American fairytale, where all people needed was a plot of land, a few kids, and bread on the table to be a success.

Ethan and Mia are the disruptors of the group and are representative of the modern millennial family, desperately trying to escape from the shadow of families like the Bakers. Mia is accepted as one of the family proper by the time Ethan arrives, and it is evident that Ethan is an outside influence the Bakers want to keep away from her. Each of them is trying to escape from the Bakers and live their own lives. Though Ethan is firmly against the Bakers and their “family,” as a couple he and Mia are hardly political; their opposition stems more from a need for survival than anything else. Together, they are the modern millennial: they have no children and no substantial contact with families of their own. They are just trying to make ends meet, and engage in politics only if necessary, or when confronted with a particular injustice.

Zoe, the sole biological daughter of the Baker family, falls into the same boat as Ethan and Mia. She disagrees with her parents’ and brother’s way of living and does what she can to put an end to it, despite knowing she can never wholly leave them behind. Zoe acknowledges her love for them but insists that they can’t keep kidnapping innocent people. Looking at various notes through the environments gives the impression that she is something of a disappointment to her parents. While Lucas is the child upholding the values of family, Zoe works against them, and so incurs their disdain.

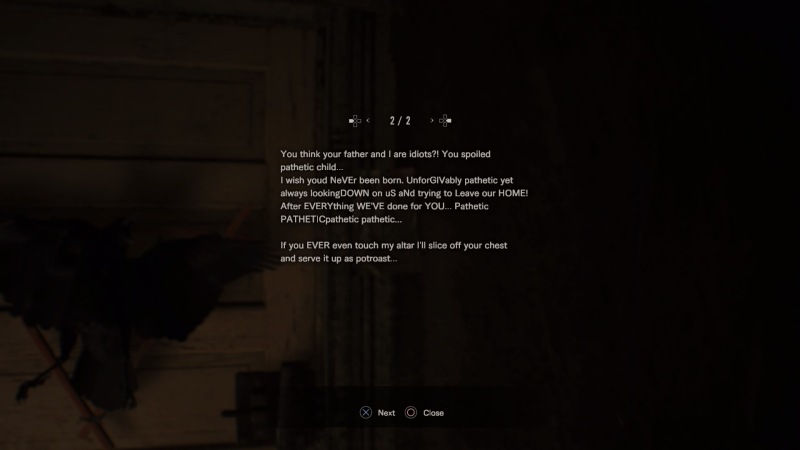

Moreso than Ethan or Mia, Zoe is a pure representation of liberal millennial youth in this analogy. Her begrudging ties to her family and efforts to stop their ways echo many of my own experiences with family. As a liberal who grew up in a conservative Christian household, Zoe’s struggle with loving her family while hating what they stand for struck a chord with me. While notes left by Marguerite berating her are almost certainly full of Evelyn’s influence as far as the story goes, their tone and diction will be familiar to any millennial who’s dealt with judgmental parents resentful that their child is going against everything expected of them.

The thread tying all of this together is Lucas. Son of Jack and Marguerite, and brother to Zoe, he’s a narcissistic 20-something with a talent for technology. Despite being the most tech-minded of the family, he is the traditionalist of the siblings, adhering to the notions of family importance. Sporting ill-advised facial hair and a hoodie, Lucas is the visual stereotype of the same brand of 21st-century good-ole-boys who sport cartoon frog avatars and use words like “triggered” and “cuck” unironically. He’s an unapologetic, unforgivable psychopathic shithead, but his importance to the game’s themes lies in that fact.

Unlike Zoe, Mia, or Ethan, Lucas doesn’t want things to change for the Bakers. Lucas is comfortable with the status quo because it ensures he can do whatever he wants to whoever he wants. Despite being from ostensibly the same age group, Lucas is content to go on with his family life, believing tradition to be the best way. At his core, this character is the embodiment of the modern conservative youth who would rail against the changing dynamics in American culture. He doesn’t do it out of a sense of deep-seated tradition like his parents, but because he’s in a position of power and wants to keep it that way.

Finally, there’s Evelyn. Less a character than a plot device, even in the main narrative, she is the representation of the childlike view of family as a safe place, no matter what. Her only want is to have a family, guided by the steadfast belief that family solves every need. She is the distillation of Jack, Marguerite, and Lucas’s worldview. More importantly, she represents the rapidly dissolving state of the American nuclear family unit.

The Baker Family ideal is an antiquated notion nowadays. For many millennials, the traditional family structure is no longer viable. Millennials have fewer children and are renting homes for prolonged periods. They are also rebelling against the political and social structures their parents continue to uphold, including issues of representation, gender, and government. Sure, Resident Evil 7 doesn’t directly approach these topics, but looking at all the characters and the roles they play, it’s hard not to think of how they might apply to this particular situation.

As the game draws to its conclusion, Evelyn’s idea of family as an infallible certainty dies with her. Between Ethan and Mia wanting to live their lives free of tradition and Zoe working to undermine her parents, the Baker idea of a family is torn apart, left to rot in the swamps. By the time the credits roll, Jack and Marguerite’s way of living has imploded. Lucas does his best to uphold his cynical worldview but comes undone eventually. Zoe, Mia, and Ethan escape from this unwanted definition of family, each indelibly changed but carrying on.

On the surface, Resident Evil 7 trades in the same body horror tropes and action hero cliches as its predecessors. But the work put into its memorable cast belies a broader set of themes than the franchise has known previously. In between the hillbilly monstrosities and bayou horror lies a potent allegory for millennial attitudes toward what we perceive as the classic American family dynamic. The characters themselves are drawn from broad stereotypes of American life, but where their interactions converge, I see the same familial strife I have come to know as I’ve started a family of my own, determined to not be like my parents. Maybe I’m putting too much thought into what is mostly a set of well-defined cliches. But I believe the subtext of any work is significant. Good art allows room for interpretation, and there is plenty to unpack in the story of Resident Evil 7.

Bad_Durandal

Bad_Durandal