I read a quote some time ago (for the life of me I can’t remember who said it) that insisted that certain genres are characterized not so much by what they are, but by what they do. Two genres that this person cited as examples were comedy and horror. Both of these, this elusive quote went on to say, incite base, almost involuntary emotions within the person experiencing them. This got me thinking about horror games and what they do to the player. Even the term “horror game” itself is a bit of a misnomer. There is, for all intents and purposes, no such thing as a horror game. It’s always a game that fits into another genre, that has the theme and intended outcome of horror.

Resident Evil 1 is a third-person puzzle/action title. Doom 3 is a first-person sci-fi shooter. Alien: Isolation is a stealth game set in a sci-fi universe. Yet, it’s this theme of horror that ties it all together. The gameplay mechanics may allow for running, shooting, jumping, crawling, hiding, or pressing buttons but it’s the emotive response players have to these experiences that characterize what a horror game can be and do. The end result is the same: to scare the player.

However, like sitting in a hot bath for a while, eventually, horror games can lose that terrifying edge, at least to some. There’s an argument to be had that exposure to something over and over renders itself moot to the player, perhaps even predictable. Now, it’s worth saying that this doesn’t mean I’ve gone off horror games. Far from it. I’ve said this numerous times, but we are currently in a golden age of horror. With tons of indie titles being released all the time, the huge success of the Resident Evil rebranding, and the new wave of cooperative titles such as Phasmophobia and Dead by Daylight, the genre is more popular than ever and churning out some fantastic games.

What I want to do in this article is share some of the most recent examples I can think of in which I felt true terror, games that got under my skin, induced anxiety, and, yes, even gave me actual nightmares.

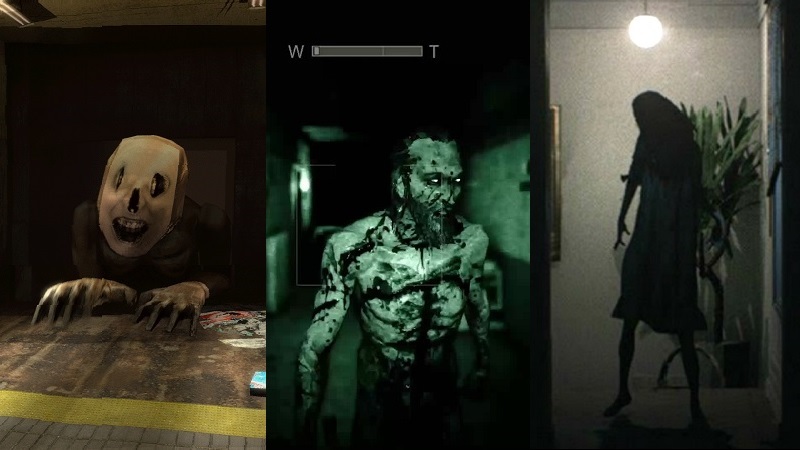

Visage

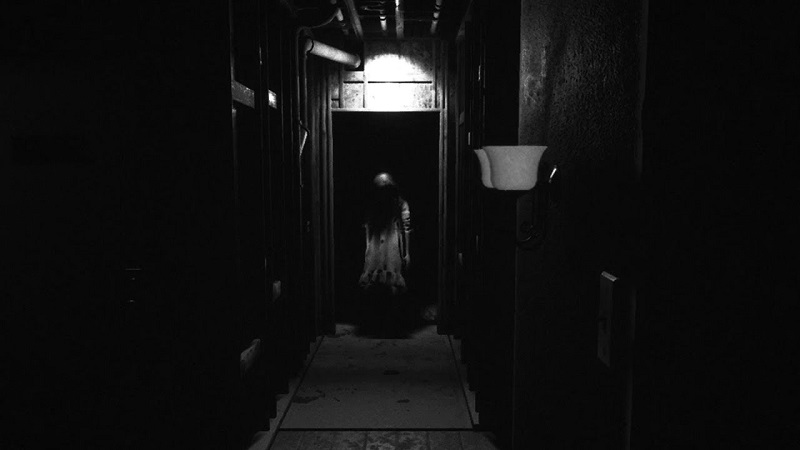

Home is safe. Home is a sanctuary. Home is where the demons are kept at bay, where locked doors barricade and protect you from the outside world. Not in Visage. What truly unsettled me about SadSquare Studio‘s first foray into horror games is the sense of not being alone. It taps into my much younger self, the wee lad who, when left in the house by himself for the evening would imagine the terror of encountering an apparition or hearing an unfamiliar sound. What this game does is take those fears I had when I was a child and actualize them in the form of a home invasion. The mysterious setting and the appearance of a ghostly menace create ambivalence about who is invading who. The game made me question who the real owner of the dark and foreboding house was, me or the past tenants who threaten the halls?

This is one of Visage‘s strongest themes, the idea that what’s familiar can also seem alien and confusing. Your home is where you know everything; the feel of each room, the sound of the stairs as you walk up and down them, which switch flicks on which light. So why does the home in this game feel in equal parts familiar and safe, yet oppressive and foreign? This is supposed to be your home, yet the mysteries of its history turn everything on its head. This is why I found Visage so effective. It takes that which is supposed to represent safety (the home) and turns it into an all-oppressive, all-consuming source of danger. This is also the first game I’ve ever played that gave me genuine nightmares. It speaks volumes about the way it sticks to the conscious and subconscious.

Our Visage review.

Outlast (all of them)

On the surface, the Outlast games are a darkly psychotic challenge that pits the player against insane brutes in a disturbing universe. But the series delves much deeper than that. Going into this section, I need to say that I’m a white, straight, cis-gendered man, so what I’m about to say relates to the way I experience games with these labels. What Outlast, as a series, does well is finding a way to come screaming at the male psyche, to come knocking like an angry landlord on the socially-constructed heteronormative ideals that engulf Western male cultures. It’s a franchise that tells me that I’m not a weak person, I’m a weak man. What is scarier than having the essence of a systemic masculine ideal viscerally proven wrong by horror games?

Outlast doesn’t care about body autonomy, as it threatens the player with cannibalism and castration. It doesn’t care about the privilege of being able-bodied, as it straps you to a wheelchair and removes a few of your fingers. It has little sympathy over the women in your life that society deems you as their protectors. It will tear and violate all masculine credentials that make up the male figure. The heroism that’s expected becomes rotten in the hands of Outlast. At a psychological level, the series makes me question what it means to be a man, in a world that rewards brutal violence yet strips me of such abilities. Not only that, but in a similar vein to Visage, Outlast creates foreignness in the player. It thrusts you into a new society, one far too unfamiliar from your own, with its own ideologies and leaders, and then you wonder why you spend the majority of the game running, hiding, and trying to get out.

Our Outlast 2 review.

Lost in Vivo

It would be entirely possible to simply leave this clip of me playing Lost in Vivo on Twitch and leave it at that. That would be enough to express the terror I felt while playing this game – even with other people chatting to me. I know it’s a common trope for streamers and YouTube Let’s Play-ers to overemphasize their reactions for the sake of views. Not in this case. That was my genuinely petrified reaction to that moment. See, what the game does, at least for me, is never give a hint as to what’s around the corner. The game excels at portraying a pure, unfiltered horror experience and turns uncertainty, confusion, and the existential discomfort of being out of one’s depths into almost an art form.

The otherworldly soundtrack buried itself into my skin, reverberating into my psyche until it became clear that Lost in Vivo did not have any intention of letting go of my attention. Even with weapons drawn, the game leaps out with its claws, though not always in a jump-scare kind of way, but in a way that removes any sense of a respite. It drew me in with its Silent Hill-esque influence, its darkly discordant noises, and its grotesque beings that threatened the mind, as well as the body. See, that’s where it gets you. That’s where all good horror games get you. It isn’t enough to shout from the darkness or to come clawing at you. It has to embed itself into you and stay there. More importantly, a game like Lost in Vivo succeeds in being terrifying by making you think “How can I be sane, in a world in which such horrors exist?” It becomes a pulsating nightmare with no end in sight.

Our Lost in Vivo review.

What it comes down to is that there are numerous ways for horror to scare us, and it doesn’t always involve a sudden shock or ear-splitting sound. There’s something about the way the above games horrified me, to make me believe in what I was seeing and experiencing on the screen.

To become jaded by horror doesn’t mean that horror itself has failed. There are some who simply cannot be scared by a game or a movie. They have learned to keep an emotional and intellectual distance. But for me, I give myself over to whatever terrifying encounters can be thrown at me. I embrace the petrifying, the spooky, the creepy, the disturbing, and the underlying themes of a horror game that crawl their way into my waking world and never let go.