In 1998, Ocarina of Time was released on the Nintendo 64. Back then it was one of the most groundbreaking titles ever to be released, featuring a large open world to explore, horse-riding, a non-linear storyline and hours of side-content to enjoy. The game was a huge hit, so we were all surprised when a sequel was released only two years later.

I could spend a good few hours rambling about how emotional and moving Majora’s Mask is, but tons of people have already done so and I’d much rather write something original. Likewise, I could also talk about the psychology and symbolism in Majora’s Mask, but recently Youtube user EmceeProphIt beat me to the punch, so I’ll skip on that as well. Instead, I wanted to talk specifically about what regular horror games can learn from this game.

Timed gameplay

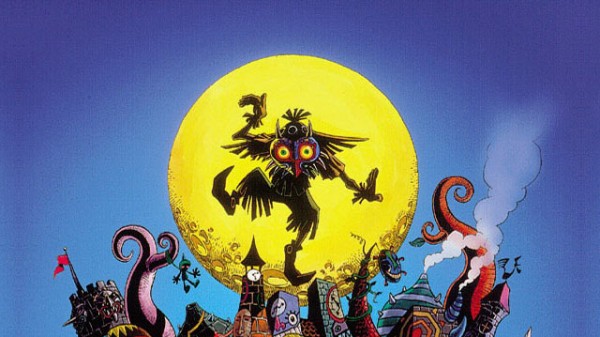

In the game, you play as a young hero who must save the world from a wooden creature called “Skull Kid,” who wears a satanic-looking mask and uses his power to drag the moon towards the earth. The game runs on a timer that lasts three in-game days, which equals roughly 54 minutes of real time. Within that time, the player can explore the world of Termina and interact with the characters to their liking, with certain events only becoming available at certain times. Everything will be fine, as long as you remember to play the “Song of Time” to reset the timer occasionally (this will make you lose non-vital items you’ve gathered, though).

Dead Rising also used a timer, but Majora’s Mask didn’t just have a timer, it at also had the moon. Our demonic-looking interstellar neighbor would come closer and closer to Termina as the timer moved on, sometimes causing earthquakes. The proximity of the moon is a much better way to make the player feel tense than having numbers slowly count down, especially when they turn around and see that gigantic face pressed against their screen. The timer affected the game in different ways, on the last day for example, the once bustling Clock Town is practically deserted, which is a nice way to make the player feel lonely. The music on the third day is also fittingly chaotic before falling away completely during the final few hours.

In short, a timer is nice, but if you work in scripted events that remind the player time is running out, it can have a great emotional effect on the player.

Uncanny valley

Majora’s Mask is kind of a weird game when you think about it; for example, a mother has lost her son at one point and asks you to find him, but instead of describing him to you, she gives you a hollow-eyed mask of his face and tells you to wear it. You then investigate around the town by talking to people while wearing the creepy thing and nobody finds it the least bit strange. Whereas most Zelda games take place in the fictional land of Hyrule, Termina is an alternate universe in which the regular rules don’t quite apply.

Unlike a game like Yume Nikki, however, the surreal elements are not blatantly obvious and shoved into your face. They are more subtle and, as a result, it always has the player feeling slightly uneasy; it’s a familiar fantasy setting that always feels slightly off. The most famous, strange element of the game is the “Elegy of Emptiness” and, more specifically, the dead-eyed statues it produces. These have become the center of many, MANY creepy pasta stories on the internet, and for good reason. There was one point in the game where I absolutely pissed myself, which was in the Stone Tower temple when I needed three statues placed to proceed. When I was done and looked back, I saw that two of them were staring directly at me while the third was blocked out of sight by a pillar.

You could argue that everything in horror is structured around the uncanny valley; even our beloved zombies represent humans that are different in ways that frighten us. Games like Silent Hill do this even better, but my point is not that we need more monsters and scary imagery, but rather that developers could strive to create worlds that are different from the one we know. If I may be so blunt as to make a suggestion, what about a world in which humans don’t have or need eyelids; it doesn’t sound scary at first, but when you simply start up a game and are confronted with it, it’s sure to leave you feeling slightly disturbed.

Emotional variety

I know that I said I wasn’t going to talk about how emotional and moving this game is, but besides being a liar, I am also a writer and emotions are a core-part of any writing process. That may sound pretty self-explanatory, but the problem with a lot of fiction is that there is little variety in the emotions. I recently played Dead Space for the first time and found the story to be utterly disinteresting, not because I didn’t like the setting, but rather because depression was the only real emotion pulling the game forward.

Majora’s Mask is also often cited to be the most depressing Zelda game out there; while that is definitely true, it also features a lot of upbeat scenes. For every father mourning over his dead son, there is a scene in which you go for a boat trip or chase monkeys through a forest, so to say. When you write a story, you can’t have it all be sad or the audience will just stop giving a shit, in other words; it would be one-dimensional. By contrasting sad scenes with heartwarming endings to side-quests and the general upbeat tone of the adventure, Majora’s Mask surpasses the title of “sad story” and instead become a “real story”, or just “story”, if you prefer. It doesn’t require a label, because it’s varied enough to stand without one.

In horror, we often want our storylines to be serious and gritty; in fact, I might be describing the entire modern video game market right there. That’s fine, though, you can have yourself a serious story, but it also can’t hurt to let the audience have a breather every once in awhile. American McGee’s Alice is a good example of this; Alice might be a mentally ill patient desperate to recover what remains of her sanity, but we have the Cheshire Cat tagging along who spends the entire game making jokes and riddles. It can also go the other way around; Left 4 Dead may seem like an action game driven entirely by humor, but there’s a pretty sad story behind it and you can find some moving moments if you pay attention.

There’s probably a few important points that I missed and if you happen to know any, then feel free to share them in the comments. Also, if you’d like to hear more about the horror elements in Zelda games, check out our Top Ten Disturbing Levels in Non-Horror games. Either way, I thank you greatly for reading this article and look forward to your reactions.